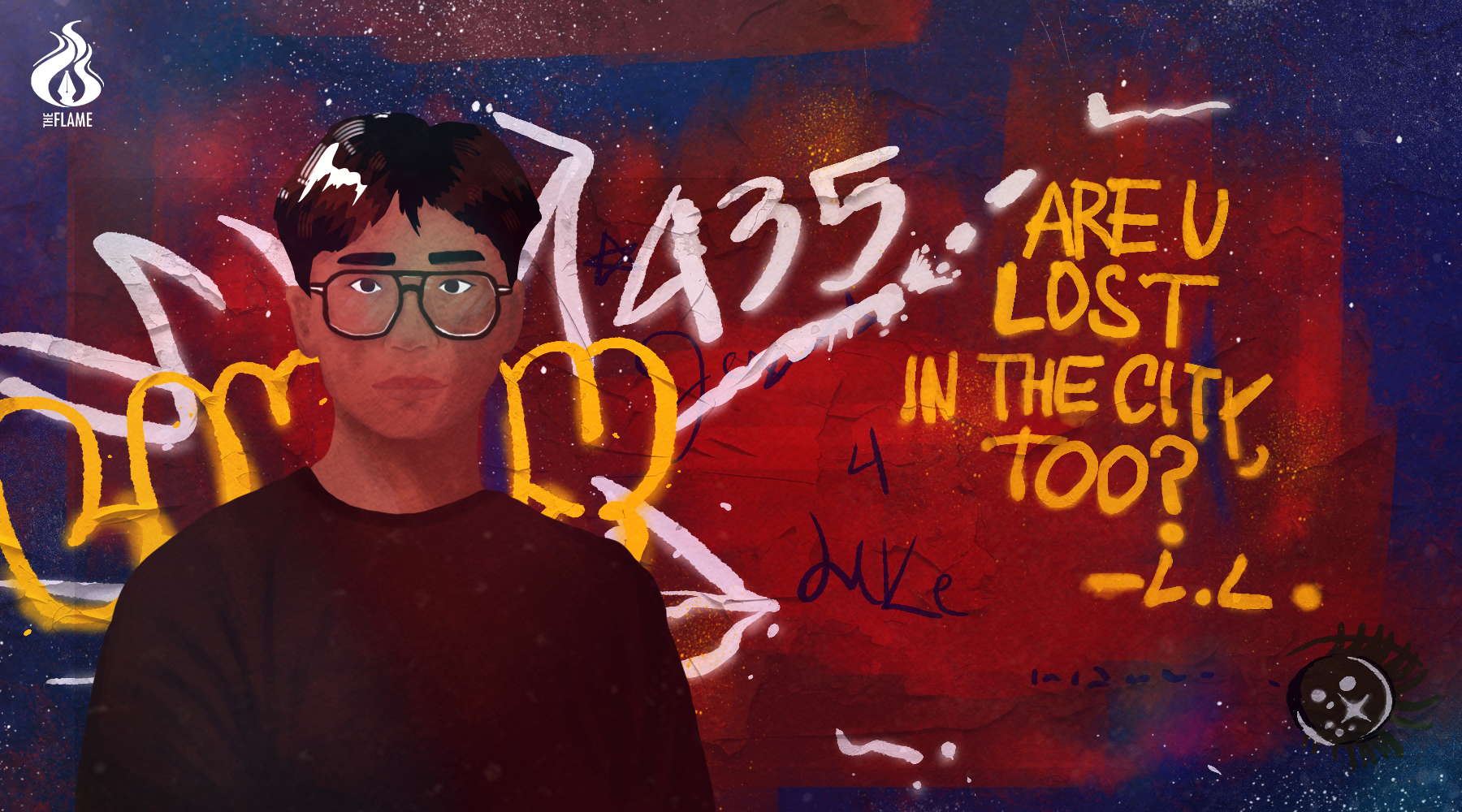

IN THE dead of the night, España Boulevard lies hushed, stripped of its daytime frenzy.

The air hums with stillness, accompanied by the soft glow of streetlights casting long, lazy shadows. No cars rumble past, no footsteps echo—just the faint rustle of leaves skittering across the sidewalk.

At the back of a southbound waiting shed near the Beato Angelico building, a lone figure moves in silence. Cloaked in a gray hoodie, he grips his yellow spray can, its hiss slicing through the silence.

It was a confession made not in a sacred indoor space, but in an open space, not before a man of cloth, but a fixture that has seen both sinners and saints kill time as they await their personal manna. It was an act that will not bring redemption but can affirm one’s faith in uncertainty.

“Why go through all these grand gestures in the name of young love?” he thought to himself.

The next day, sunlight bathes España, bringing the boulevard back to life. Students and professors spill from lecture halls, all of them already used to the historic area where Asia’s oldest university stands.

But there is always something new for those with keen eyes to see.

For others, it is a punchy question sprawled across the back of a waiting shed. For some, it is more than a fleeting wink but a nudge to the soul.

“ARE U LOST IN THE CITY, TOO?” the enigmatic “L.L.” posed to passersby.

For months, L.L.’s sly, tender and unapologetic graffiti lit up screens, with each viral post a nod from strangers, including Thomasians, who saw their own aches reflected in his words.

As España’s “relapse” phantom, he spoke on behalf of those who yearn and who reside in a metropolis that rarely pauses to listen.

From quiet roots to loud churns

While L.L., or Love Limmy, has become the mysterious conveyor of Manila’s unexpressed thoughts, he is no native of the noisy capital city.

Hailing from the hushed fields of Quezon province, he stepped into the city as a college freshman, wide-eyed and rattled by its pace.

It was a sticker on a campus sign that stopped him in his tracks: a small, brash tag waiting to be seen. It was a jolt. It was a sleek, black-and-white logo that resembled the Chanel logo—nothing fancy, but also not quite like anything L.L. had seen before.

“It had… style,” he thought.

“I wanted to leave my mark, too,” L.L. told The Flame. “It’s like telling a statement, ‘I was here and I exist.’”

An essayist and multimedia artist whose forte is filmmaking and photography, he drew from his creative roots to reflect his shift from a small-town kid to a mysterious messenger who makes people see the writing on the wall – quite literally.

The half-whisper, half-cry, ‘Ano ba talaga tayo?’ (‘What are we?’) first hit the waiting shed as a dagger to the young love’s confusion, followed by the fierce yet frail, ‘I deserve love, too, as much as anyone else.’

His first tags were impulsive, born in the blur of midnight strolls, each piece he described a “trivial yet grand gesture.”

“But I think that’s just how it is: everything feels unbearably tremendous when you’re trying to make sense of things,” the artist said.

“That’s what we do when we’re trying to find love; we romanticize our pain and hope someone gets it.”

What began as a private exhale became public poetry. L.L.’s tags weave heartbreak and hope into Manila’s skin.

Love, in all its messy shades, became his muse.

Creator or violator?

On April 8, L.L. unmasked his identity in a face reveal interview. For casual followers, it’s a solved riddle; for him, it bared the tightrope of his art, teetering on the law’s edge.

After all, laws do not bend for inspiration.

Lawyer Marie Elinor Flores of the Manila City Legal Office said taggers caught mid-act may face charges under City Ordinance No. 7971 or the 1999 Anti-Vandalism Law.

According to Flores, offenders may face court-ordered civil or criminal compensation, provided due process is followed.

“If it’s city jurisdiction like roads and parks, the city is the complainant,” Flores told The Flame, adding that graffiti damaging private property could be deemed malicious mischief.

Individuals found guilty of violating this ordinance could face a fine ranging from P1,000 to P5,000, imprisonment for a period of six months to one year, or both.

Concerned citizens may also report incidents to their barangays, local police stations, or directly to the city hall. Authorities are expected to act on the report within 72 hours.

Yet, cracks exist; the lawyer noted that enforcement often falls short, particularly in maintaining cleanliness.

“It can be coordinated with the concerned barangay, and they can take action to clean the surroundings. But there are times when issues arise [in barangays] with funds or budget,” Flores said.

“If no one files a complaint with the concerned offices, it’s hard to take action,” she added, citing the difficulties in addressing complaints when they go unreported.

For L.L., his graffiti is both a refuge and a risk—a leeway to create, but always with a glance over his shoulder.

But he finds grit in the defiance of famed graffiti artists, some of whom are gallerists who have documented their works online.

“If they can do it, why can’t I?” he said.

Who lets the walls talk?

Graffiti has long been a form of protest and resistance, with some scholars considering it a form of micro-level political participation. Activists used walls and public spaces to write slogans and messages opposing oppressive regimes, often calling for freedom, justice and an end to dictatorship.

The Philippines, a developing country grappling with economic hardships and social inequalities, has its own version of the street art. Often seen in crowded areas like Sampaloc, Taft, or Quiapo are stickers placed on lampposts with cryptic tags or pop culture riffs and spray-painted throw-ups on concrete, some of them carrying sharp social jabs.

Shortly after L.L. unmasked himself on X (formerly Twitter), critics pounced on him, raising questions about his fixation with graffiti, which was deemed by some as incompatible with his status as a student of a prestigious school in Manila.

“We commonly associate graffiti with those outside of these [prestigious] circles in the first place; I guess that’s a bias we have to eliminate,” he said.

“We think they’re just damage to property, which to some extent, really is. But I don’t think much people are aware that graffiti had its roots in activism.”

The artist, however, draws the line when it comes to comparing his hugot sprays to other graffiti, believing it is a “disservice” to actual issues that need visibility.

“It’s still important to recognize that graffiti is also a tool used by marginalized sectors and advocates to amplify their causes,” he said.

For L.L., the allure of graffiti lies in its boldness—its power as a medium that challenges limits to make a statement.

“That’s one of the reasons why a lot of graffiti artists, aside from myself, get to enjoy the liberty or the notoriety that comes with graffiti,” he added.

Acknowledging the reach of the medium, L.L. emphasized the nuanced contexts in creating unconventional and taboo art forms.

“It feels rash to have these decisive stances on graffiti without being more critical about it,” he said.

“Graffiti is really a wide sphere. Some artworks are created for commercial purposes, while others are driven by advocacies. Just like how institutional art is.”

Keeping it authentic

Despite gaining traction for his street art, L.L. maintained that his graffiti is not meant to chase clout. For him, it is his way to “crash out,” not a show for a hungry crowd.

“It feels inauthentic to force yourself to keep doing more, to keep creating more, just because there’s a demand,” he said. “I wouldn’t really want to tap back into that sort of state of mind.”

For now, the small-town dreamer turned urban poet has spun España and is bent on using his messy spray cans to express what is often suppressed and to reflect on things that are usually left to neglect.

“To some degree, I like to think the stuff I write through graffiti can be life-changing or at least spark some kind of epiphany in someone,” he said.

Art or offense, these walls speak; and the city, willingly or not, hears his truth.

“For me, it’s cathartic. I’m writing a brief summation of my feelings for Manila to see, and somehow, that makes me feel less alone while navigating failed relationships,” he said. F