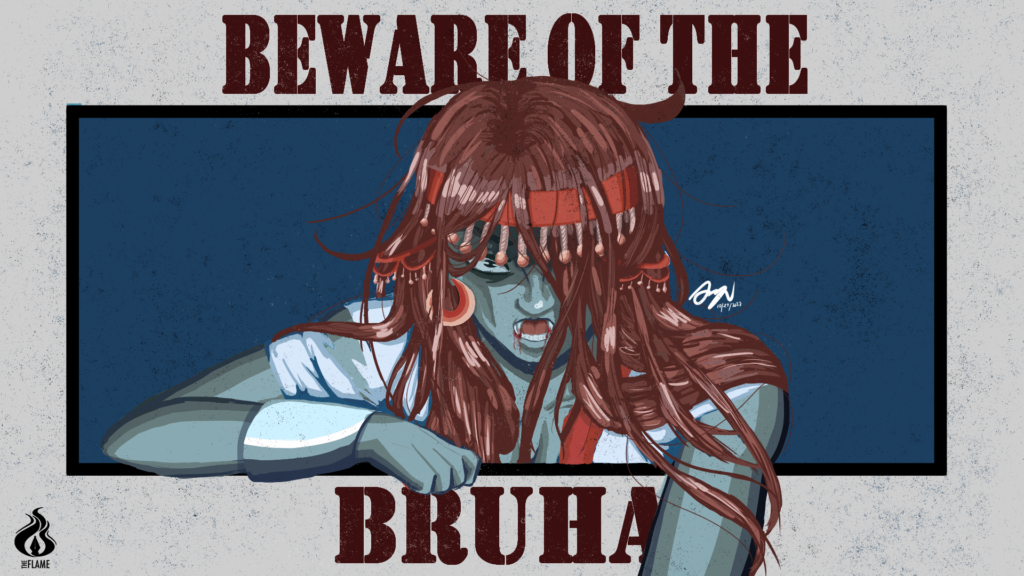

Art by Marie Alexa B. Natividad / THE FLAME

WITH UNFALTERING courage, the Filipino woman perseveres daily. She works, she feeds, and she heals. Her contribution to society holds half the sky in restless adoration, despite actions invalidating her effort.

In these dated ideals come images of the “ideal” Filipina—stereotyped as modest, saintly, and submissive—a Maria Clara.

However, before conjured colonial images of the Filipina were the Babaylans: women and feminine-presenting men who served as shamans and spiritual healers to native Filipinos.

Due to colonial influences among early Filipinos, the Babaylans became targets of malicious propaganda by Spanish missionaries who aimed to convert the local religions to Christianity. From being esteemed spiritual women, the Babaylans were branded as bruhas and mambabarangs, or witches in English.

As times became modern, manifestations of pre-colonial beliefs continued to exist despite modernization and progress. Propaganda plagues her, half the sky resting on the palms of misunderstood women.

The woman, the myth, the legend

The concept of myths being used as a weapon to control people is not uncommon in the Philippine context.

According to Assoc. Prof. Augusto de Viana from the University of Santo Tomas Department of History, the phenomenon happened as early as the pre-colonial period.

In the 16th century, Spanish missionaries waged war on native religions by inciting fear among the natives through the demonization of Babaylans.

De Viana explained that it was believed Babaylans were in contact with the spirit world with Gods communicating with them directly. This connection gained Babaylans influence over barangays through their service to Datus, the pre-hispanic leaders of communities.

To Spanish missionaries, the recontextualization of Babaylans as evil entities like aswangs would mean more converts. The disempowerment of the Babaylans was also the disempowerment of Filipinas in general as the missionaries did not only take control of women’s spiritual beliefs, but also their bodies, according to the study, “Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines: Struggles, Advances, and Challenges”.

De Viana continued, saying that just over three decades ago, the phenomenon of fear as discredit happened again during the Cory Aquino administration.

During the height of the New People’s Army (NPA) insurgency, the Philippine government adopted the psychological counterinsurgency tactic the United State’s Central Intelligence Agency used to defeat the Hukbalahap Rebellion during the 1950s.

Instead of Babaylans, the Aswang myth was utilized, creating the story of a flying creature whose lower region was severed and was reported to be seen around the country, including urban areas. Due to this, the NPA’s movement at night became restricted.

“The communists are not supposed to be afraid because they are supposed to be atheists, right? But if they were actually atheists, why did they believe in otherworldly creatures?” de Viana asked rhetorically.

‘Tao po!’

Though both Aswang and Mambabarang were used as propaganda, de Viana emphasized the significance of noting the difference between the two.

De Viana contrasted Aswangs and Babaylans by identifying aswangs as inherently non-human, but bruhas as actual people, both meeting as a means of control and fear among populations.

“The power of women became severely weakened because of this branding; [because of] the misogyny of the Spanish colonizers,” de Viana said.

In addition, he said that women’s power became severely weakened because of the branding created by the misogynistic Spanish colonizers.

Unlike Aswangs, the demonized Babaylans were real women who were falsely deemed evil so that they would be driven out of power.

The ‘Babae lang’ today

From leaders of religious rituals, Filipinas’ role in a community was greatly reduced due to colonization. To de Viana, it is only recently that these means are being retrieved against the deeply-embedded culture of misogyny the colonizers had brought to the country.

With women gaining the right to suffrage in 1937, the recovery of an equal social order is in progress, albeit gradually. According to the latest Global Gender Gap report, the Philippines ranked 17th among 156 countries with 78.4% of its gender gap being closed.

Nonetheless, Filipinas still struggle against being targets of disinformation. In a study conducted by the United Nations Population Fund and UN Women, 26% of social media posts in the Philippines between September 2019 and November 2020 contained misogynistic notions, victim-blaming of assault survivors, and misconceptions about women.

Manifestations of pre-colonial practices still exist today as well, signaling that despite consistent propaganda, the service of Babaylans survived. “Do you ever wonder why in Quiapo, the fortune-tellers and healers are all women?” de Viana asked. “That’s a part of our Babaylan ancestry manifesting itself. They either conceal themselves on purpose or are simply hiding in plain sight.” F – V. Mendoza