TO BEAR the brunt of the blame for something made to destroy humanity is a huge burden on one’s shoulders. However, who gives anyone the right to make that decision?

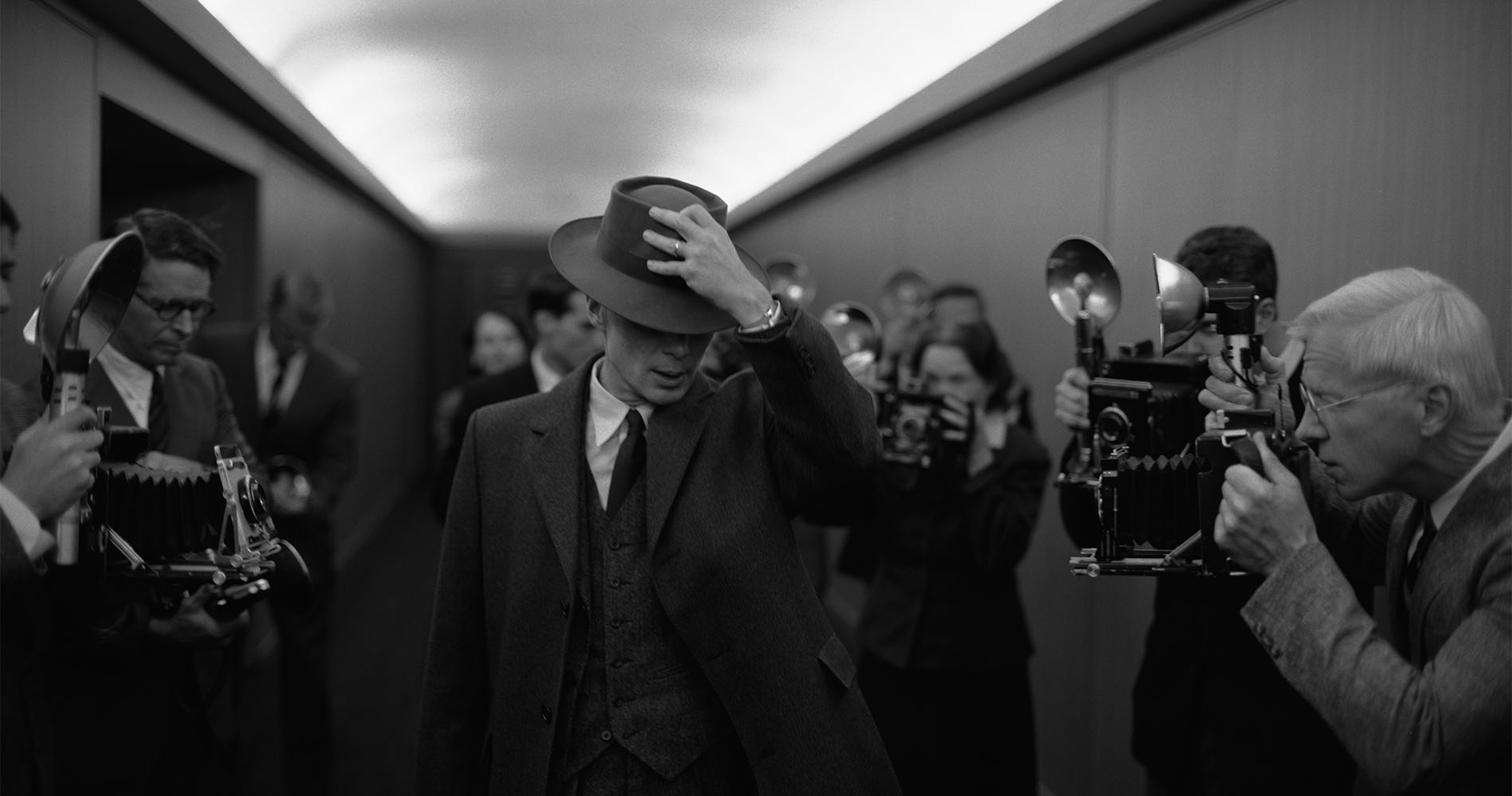

Oppenheimer succeeds in showing the horror of making a weapon of mass destruction but more so the moral confusion that nagged J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), widely known as the ‘Father of the Atomic Bomb.’

Based on the biography written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin titled American Prometheus (2005), the Christopher Nolan film follows Oppenheimer’s life in several parts.

The film depicts his life from being a physics student in 1920s England and Germany to a pioneer professor of quantum physics in the United States — all the while being involved in left-wing groups such as the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians and the Communist Party USA. Soon he gets tapped to head the Manhattan Project, done in Los Alamos, New Mexico, erupting into the climax of the creation (and detonation) of a nuclear device. Using different timelines and points of view differentiated by color, the three-hour biopic shows Oppenheimer’s enigmatic character.

Nolan’s use of IMAX cameras allows a more expansive approach in his filmmaking, but more so in this film. Its grand set piece, set in the middle of the desert at dawn, is shot beautifully and would not be as immersive if filmed with regular cinema cameras. The use of this format allows Oppenheimer to put large amounts of detail into its overall design, blocking, and shot composition — as if having a larger canvas to paint with.

The incredible sound design, especially within the climax, takes the experience of the film to a whole new level. The radiation ticks of uranium-235 as one would hear in a Geiger counter as it is nearing completion, the delayed boom of the atomic bomb in the desert, not to mention the immense score of Ludwig Göransson, carries the film’s momentum further.

However, it will be a remiss to say that only its technical merits deserve applause. The elite ensemble of actors that Nolan has at his disposal certainly proves to be one of the film’s strongest points: Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) as Oppenheimer’s colleague and bitter rival, Kitty Oppenheimer (Emily Blunt) as Oppenheimer’s wife, and Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) as Oppenheimer’s on-and-off lover are just some of the stellar performances in the film. The rest of the supporting cast play their roles remarkably as 20th-century scientists and officials even with their shared minutes on screen.

But to talk only about the bomb’s detonation would entirely miss the point. All along the story is the talk on ethics and morality in creating such a weapon for mass destruction; a certain ambiguity surround Oppenheimer acts and motivations.

To create a bomb capable of destroying the world — an invention that only Oppenheimer and a handful of people could do — is the scientists’ ethical dilemma. The film shows the unchecked power that people hold in their positions, and asks repeatedly whether it is right to have such an authority — the authority to make such a weapon, use it against one’s enemies and shape the world through nuclear warfare. It deliberately questions the many forms of authority seen throughout the film: in politics, science, and war.

It portrays Oppenheimer as a tortured genius. Everything within Oppenheimer happened within his context and his understanding. The destruction caused by his inventions is only seen through his eyes and through the data and news he receives. Its effects on the Japanese populace is never shown, only its physical manifestations through his vivid hallucinations. Focusing only on his point-of-view clearly shows the mental anguish he is going through and cements the horror of his creation to great effect.

Still, there are moments when the film loses itself in the slowness of some scenes as well as its complexity just to accommodate the big picture. With such a long runtime and a lot of information, there are times when the film is difficult to follow, especially when the dialogue and soundtrack are on top of each other.

Oppenheimer ultimately tells a story of the doomed scientist and the dilemma of progress. The film leaves its audiences with harrowing thoughts about the state of the world, due by and large to the well-rounded characterization of Oppenheimer and the technical precision one would expect from Nolan. It shows the enormous power a person, entity, or government can have, and questions if they are worthy to make decisions on matters of life and death — and ultimately if anyone is worthy to have that power at all. F – Robb Nigel Moya