AS LAWMAKERS propose ways to improve transplantation in the country, a UST Theology and Biological Sciences professor warned that monetizing organ donation could “corrupt” the system and “coerce” Filipinos into donating.

During a hearing at the House of Representatives, Fr. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, O.P., chair of the National Transplant Ethics Committee (NTEC), criticized a bill seeking to provide benefits for donors, saying it could lead to organ commercialization.

“Any act of organ donation must never include an exchange of financial assistance between the recipient and donor, even after the donation has been made. Allowing this would corrupt our system by creating a loophole for the commercialization of organ exchange,” Austriaco told members of the House health committee on Jan. 28.

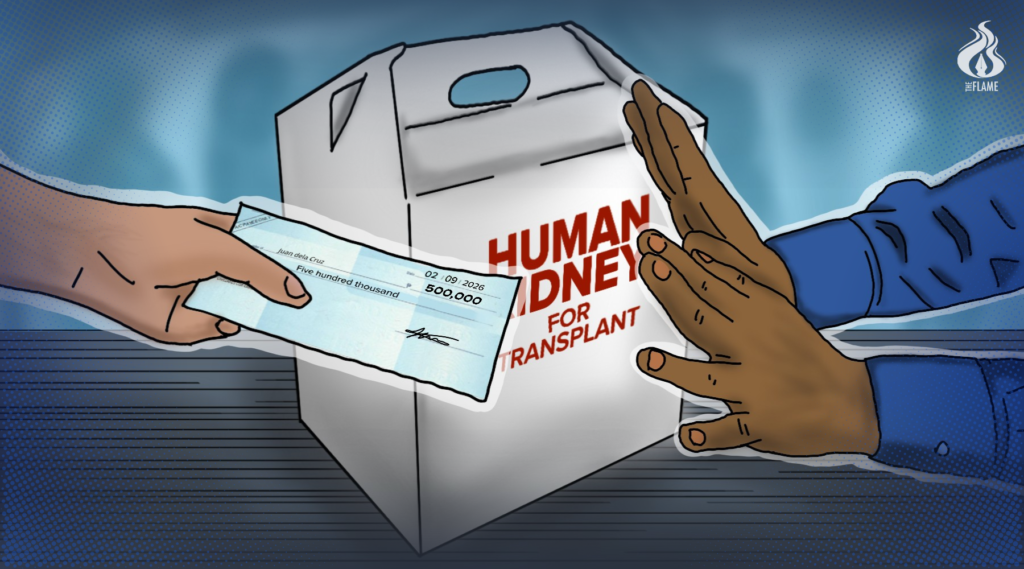

According to Austriaco, House Bill 4287, which offers P500,000 or its equivalent in financial assistance through funeral subsidies, educational assistance or livelihood support for the donor’s family, is “unethical and potentially exploitative.”

“The ethical challenge of providing financial remuneration, especially P500,000, is that it becomes coercive. So imagine if you are a poor Filipino and your family is making P500 per day,” Austriaco told The Flame.

“Kuya (brother) died. And in the middle of the grieving, you find out that you will receive half a million pesos if you give kuya’s body to the hospital. Can you say no? Impossible. That’s equivalent to three years of wages,” he added.

The NTEC is a government committee under the Department of Health that establishes ethical guidelines and policies for organ donation and transplantation to curb organ trading and protect donors from exploitation.

Citing the Istanbul Declaration of 2008, a document tackling organ trafficking, the Thomasian professor said organ donation must be “financially neutral,” meaning no benefits must be provided for donors.

“To be financially neutral, you can receive money, but it has to compensate you for loss that is directly related to the organ donation,” Austriaco said, referring to medical procedures.

“If you want to give a kidney or a liver, and you have to stay in the hospital, the government can pay for your confinement. The government can pay for your hospital bills… But you see, these are neutral. You do not gain financially from the donation,” he added.

‘Family-in system’

The NTEC chair also opposed House Bill 2226, which proposes an opt-out system that automatically considers everyone a donor unless one formally registers his or her decision not to donate.

Austriaco, a Dominican priest, said the policy would be “unethical” because it presumes most citizens are willing donors.

He cited a 2021 survey wherein only 55% of 385 respondents who were driver’s license applicants in Metro Manila said yes to organ donation.

“In light of this evidence, it would be unethical to impose an opt-out program on the Filipino population,” Austriaco said.

“An opt-out system would erode the trust that Filipinos have in their healthcare professionals… [It] would force Filipino families to fight their doctors and nurses if they do not want to surrender the family members’ organs for donation,” he added.

Instead, the NTEC chair proposed a “family-in system,” which would require an individual to consent upon the approval of their family. According to him, organ donation is a family decision.

“It has to be family in, not just opt-in. It has to be the family that agrees to give…Otherwise, it becomes complicated, because in the hospital, if mama and papa did not know that kuya gave, it will cause problems,” Austriaco said.

Once Filipinos are properly informed about organ donation, a “mandated choice” should also be implemented alongside the existing systems, he added.

“Mandated choice is… We will not tell you how to choose, but we will force you to choose… And the idea is that whether you choose to give or not is not the issue. We would like you to give, but we require you to choose,” Austriaco said.

To encourage more people to become organ donors, the professor said reforms should go beyond legislation and include changing the country’s culture and attitudes toward donation.

“For example, Batang Quiapo, right? So, if we have in Batang Quiapo, there is a story about organ donation and how it’s helpful and doesn’t hurt you. You can imagine it will influence our people,” Austriaco said.

“It’s not just the law. In fact, the law is the minimal thing. It’s really education, public relations, cultural narratives that have to be changed.”

Austriaco serves as a professor at UST, where he teaches Sacred Theology and Biological Sciences and conducts studies on vaccines and cell biology at the Research Center for the Natural and Applied Sciences.

The hearing tackled five House bills that seek to amend Republic Act 7170 or the Organ Donation Act of 1991. F