WHEN HE entered the gates of the University of Santo Tomas (UST) and walked past the Arch of the Centuries, Communication Arts junior Alexander Guevarra was convinced he was safe within the walls of the campus. “Akala ko ‘yung UST, safe space siya para sa lahat, [a] harm-free environment.”

But now, Guevarra no longer sees UST as a top-of-the-line institution, all the more as one of the finest Catholic universities in the country after the fatal hazing case of Civil Law freshman and Political Science alumnus Horacio “Atio” Castillo III.

On Sept. 17, Castillo was declared dead on arrival at the Chinese General Hospital, following the “welcoming rites” of Civil Law-based fraternity Aegis Juris that he attended a day before.

Aegis Juris member and suspectturned-state-witness Mark Anthony Ventura earlier disclosed to Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II that Castillo received numerous punches and five paddle hits from frat men until his veins ruptured. The victim lost consciousness after the fifth paddle hit allegedly delivered by Aegis Juris “Grand Praefectus” Arvin Balag.

Balag, however, refused to answer questions from the Senate public order committee about his position in the fraternity during a hearing. He was cited for contempt and was detained at the upper house on Oct. 18.

Almost two months later, the Supreme Court ordered the release of the suspected fraternity head from detention, following a petition he filed on November.

This year, the Department of Justice panel of prosecutors reopened the preliminary investigation on Castillo’s case after receiving Ventura’s affidavit, in which he named the Aegis Juris members who carried out the hazing rites.

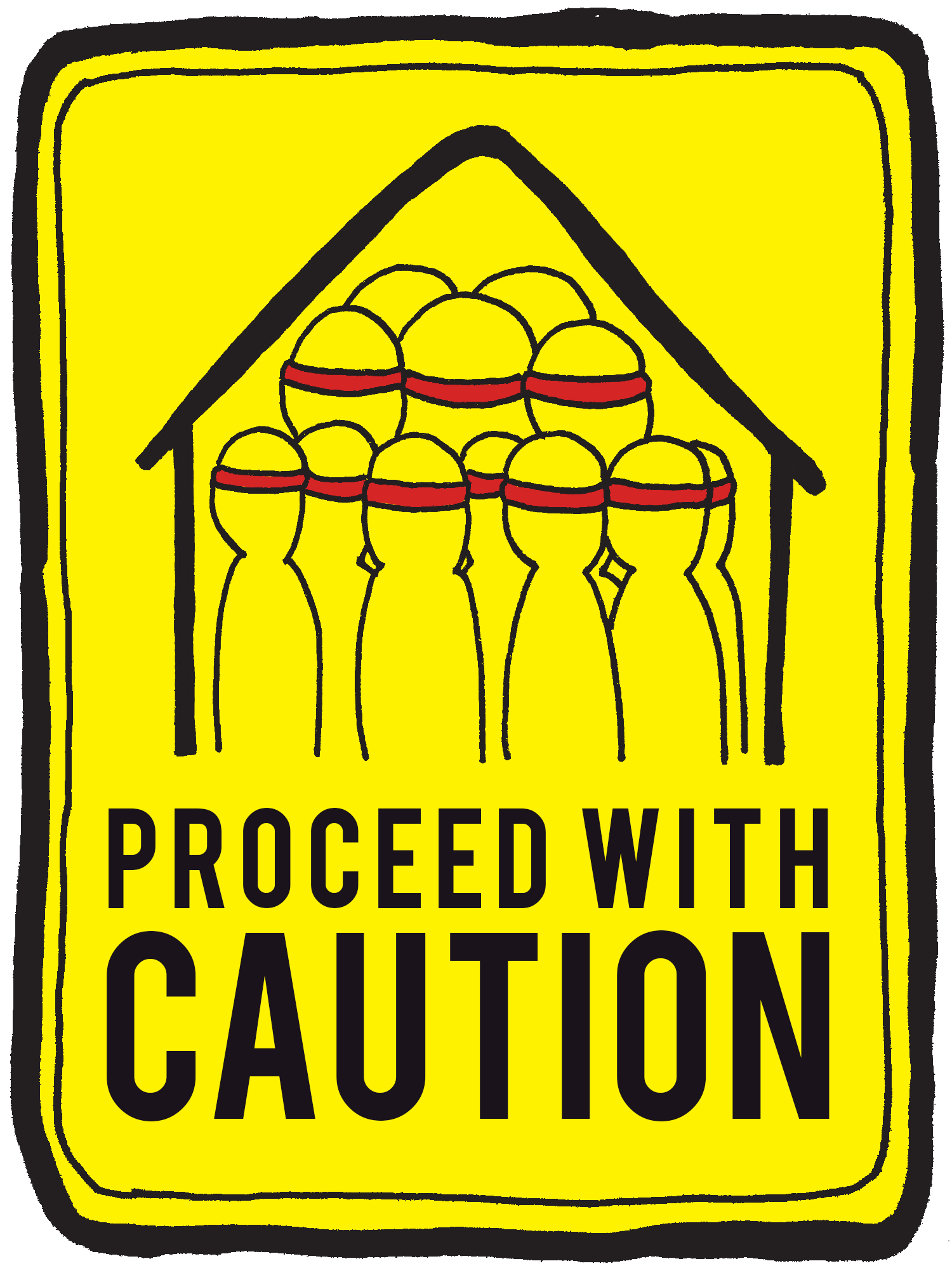

In light of recent events, the public, especially the Thomasian community, is clamoring for information on UST’s ongoing investigation on the case, and its plans on ensuring the safety of its students.

Following the blood trail

“Kung ikaw sa kapatid mo, bago mo ba siya tawaging kapatid, sinaktan mo ba muna siya? Sinaktan ka ba muna niya? Ipinahiya ka ba muna niya bago ka niya tawaging kapatid?”

This was the question raised by Arts and Letters Student Council (ABSC) Vice President-External Jancisko Valera on the intention of fraternities and sororities to conduct hazing to neophytes. For Valera, there is a need to address this kind of practice to avoid violence.

Behavioral Science senior Dana Sapno recalled how she used to see Castillo at the halls of the Faculty of Arts and Letters, adding that joining an organization is an individual’s effort to find a sense of belongingness.

With Castillo’s case in the limelight, UST administrators earned flak from several lawmakers after loopholes on the recognition of fraternities and sororities in the University and the regulation of these organizations’ welcoming rights were found in the Student Handbook.

Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian told the Flame that he had already suggested to Office for Student Affairs (OSA) Director Socorro Guan Hing that an underground investigation on fraternities and sororities be conducted.

“Hindi naman sasabihin sa’yo ng bata na dumaan siya ng hazing, ‘di ba? Pero there are ways to know [about it]. Mag-investigate ka; magpadala ka ng parang magkukunwaring [neophytes]. Magkaroon ka ng informant, intelligence, so you would know. Kung hindi, hindi mo talaga malalaman ‘yan,” Gatchalian said.

UST Rector Herminio Dagohoy formed a committee to investigate on the case, according to a statement from the University released after news of Castillo’s death broke.

The Flame sought the Office of the Rector for details about the investigation committee but was instead advised to seek Guan Hing who was the head of the said group. She has yet to respond as of press time.

Secretary General Jesus Miranda said information on the University’s internal investigation, revisions in the Student Handbook, and concrete actions to be done following Castillo’s case will only be disclosed to the public once the investigation of the committee is finished.

Central Student Council Secretary Therese Gorospe echoed Miranda and believes that UST does not have shortcomings in dealing with the hazing case. “[Noong lumabas ‘yung balita,] tinawagan ako ng OSA director na may committee na ginawa si Father Rector for the case. So I think pagkaalam pa lang ng nangyari, gumawa na agad ng action ang UST.”

ABSC President Reymark Simbulan acknowledges the efforts of the administration but said it should be more transparent about the progress of the case.

“UST is doing their best but I think they can do so much more,” he said. “What they want to have is private investigation […] pero hindi magwo-work ‘yung bagay na ‘yun kung sila lang ang nakakaalam.”

Looking at the bigger picture, many stakeholders, including lawmakers, found that Republic Act. No. 8049 of 1995 or the Anti-Hazing Law has limitations and loopholes which may pose a threat to the resolution of hazing cases. How are legislators planning to remedy this issue?

Plugging the loopholes

The Anti-Hazing Law regulates and allows other forms of hazing except for infliction of physical harm.

Under the said law, people who are directly involved in the infliction of harm will be penalized, while those who have actual knowledge of the hazing and are present during the act but did not do anything to prevent it can be considered accomplices.

However, the Anti-Hazing Law provides penalties only when a victim suffered physical injuries or death.

Previous reports showed that hazing in fraternities and sororities in the country resulted to 18 deaths and 393 suspects since 1995. With all these, the only conviction under the law was with the case of Marlon Villanueva, a student from the University of the Philippines Los Baños, in 2006.

Titled “a law regulating hazing,” the Anti-Hazing Law is put into question by Gatchalian and Sen. Richard Gordon.

Gordon, chairperson of the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights, clarified that the said law prohibits hazing or any initiation rites in any form without prior written no tice—a source of conflict because “nobody gives you a notice for hazing.”

Gatchalian pointed out this complication. “It (Anti-Hazing Law) sets up procedure for hazing. You have to inform the school [when an initiation is to be done] pero wala namang penalty kung hindi ginagawa ‘yun. So walang gumagawa noon kasi ‘di naman mapaparusahan.”

The lack of witnesses due to being bound with the so-called “code of silence” is one of the reasons why difficulty arises in filing charges against individuals involved in hazing, Gordon said.

“Simply say no hazing in all fraternities and [put] severe punishments on those who will continue the malpractice of hazing,” the justice and human rights committee chairperson suggested.

Gatchalian, in his Senate Bill 199, similarly proposes that hazing in all forms be prohibited and that registration of all organizations in their respective institutions be mandatory.

“[P]ut more responsibilities to the schools. Dapat very clear ‘yung kanilang responsibilities. […] Two, dapat clear ‘yung law na kung ikaw ay gumagawa ng bagay na pagtatakpan mo ‘yung crime, kasama ka rin sa mapaparusahan,” the senator added.

Efforts from lawmakers and other people concerned in the issue exist but until Castillo’s case is resolved, Legal Management freshman Melissa Uy can only express her disappointment with the silence offered by the UST administration.

“When people start watching you for your values and principles, saka sila umiiwas—parang hypocrisy at its finest.” F MARY ADELINE A. DELA CRUZ and ALYSSA MAE S. RAFAEL