By HALEE ANDREA B. ALCARAZ and ANA GABRIELLE CEGUERA

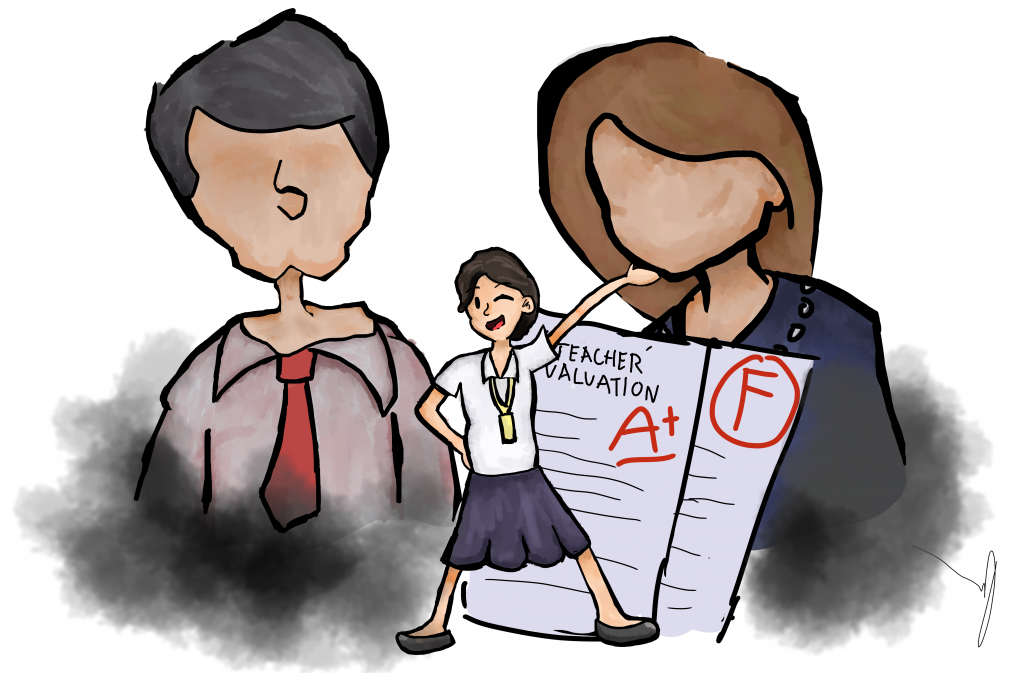

GONE are the days when lecturers and professors can execute their individual teaching strategies without students having a say on it. The University requires that for excellent education to be achieved, it has to listen to its indispensable stakeholders—the students—through a “comprehensive” faculty evaluation.

However, as the students evaluate their teachers’ performances every semester, they have not been convinced with the effectivity of the faculty evaluation in improving the professors’ pedagogies; faculty members themselves are divided on whether or not the evaluation process yields any change.

Encouraging growth

The main purpose of the faculty evaluation is for the faculty members to become better college educators, Assistant Dean Nancy Tabirara said.

“It’s a way by which we are able to ensure the fulfillment of the objectives of the programs and all of the college as a whole,” she said.

The standardized evaluation is prepared by the Office of Faculty Evaluation and Development under the Office of the Vice Rector for Academic Affairs. Its primary objectives are to enhance the instructional methods, promote sound education principles, provide monitoring assistance to the university, and assess the performance of the pedagogues.

The evaluation has two parts: first is the objective part where students grade the performance of teachers presented in a questionnaire assessing their strategies, mastery, professionalism, and the like. Second is the subjective part where students are given a free space where they can comment down their appraisal, criticisms, and suggestions for a particular teacher.

Determining a professor’s competency

Some department chairs said the faculty evaluation is essential in fulfilling the responsibility of the University in giving quality education to its students as it allows educators to improve their pedagogical approaches.

“I think it’s not just for the Faculty of Arts and Letters (AB) but for any institution, especially an educational institution, feedback is an important component,” Asst. Prof. Camilla Vizconde, chairperson of the English department said.

This is because feedback provides “centric responses” on the implementation of different curricula and strategies, as well as teachers’ capacities in ensuring high-grade education, she added.

Department of Sociology Chairperson Asst. Prof. Josephine Placido asserted that this process is “very important” because there are some teachers who are not performing well.

Meanwhile, for journalism lecturer Asst. Prof. Leo Laparan II, the evaluation personally helps him adjust to students’ needs.

“I have to make sure they get the most out of the money that they paid [with], so one simple way of making their tuition worth [it] for them is pumasok everyday, magturo and make sure na tinuturo ay maayos and na may natutunan sila everytime they get out of the classroom,” he said.

The consequences of low grades

Having a low evaluation grade has possible repercussions, Tabirara and some department chairs told the Flame.

It is the program coordinators who give the evaluation results to the professors. When there are concerns or problems that need to be addressed, the dean calls for a face-to-face meeting with the teacher together with the department chair to discuss the evaluation results.

The result, which implies a measure of the competency and abilities of a teacher, also determines whether or not an instructor on probation or a part-time faculty member will be rehired.

Placido said that in her several years in the Faculty, during which time she served as one of the administrators and a member of the Faculty Council that oversees the teachers, there have already been various cases where a teacher was not rehired because of a low evaluation grade.

“The University is very particular to put a professor or the teacher in the probationary. We have to see at least three or four years of their student evaluation. If they will be safe, they will be recommended for a probationary or tenureship,” she said.

If a teacher is on probation, his or her three to four years of teaching will be monitored through the results of evaluations. On the other hand, a tenured professor has a permanent position as a faculty member.

No aid in improvement

However, some faculty members are not completely fond of the effectivity of the faculty evaluation.

Filipino professor Dr. Roberto Ampil said the evaluation does not fully determine a teacher’s efficiency to teach a subject matter because there are students who do not take it seriously or there are some who give low grades because of disinterestedness in the course.

Citing academic freedom, Ampil said a teacher should not be dictated on how to handle his or her classes.

“Hindi ibang tao [ang] magsasabi sa’yo kung anong dapat gawin mo, kasi no matter na gaano kaganda ‘yung sinasabi nila, pag in-apply mo na, hindi mo rin magagawa, so talagang ikaw pa ring teacher, kapag ando’n ka na, nakalublob ka na do’n. Ito ‘yung klase ng estudyante mo, so i-a-apply mo ‘yung sarili mong strategy,” he said.

Moreover, the evaluation does not really say much about teachers’ performances because of students’ “random comments,” Dr. Paolo Bolanos, chairman of the Department of Philosophy said.

“Sometimes the concerns are not even related to the course content, or the specific pedagogical style of the faculty. Minsan napaka-personal, napaka-subjective,” he added.

Students’ stance

If faculty members are divided on their stances, students are no different.

History freshman Wida Echalar posited that the assessment is only “a little effective” for the same reason as Ampil: some students do not take it seriously.

“Maybe it’s because the evaluation is too long and it gets boring to accomplish along the way,” Echalar said; even the teachers themselves give little regard to the evaluation results, she added.

Further, she said some professors and instructors would still stick to their old way of teaching regardless of the evaluation results “rather than give the students the quality education they really deserve.”

A senior history major who asked for anonymity also claimed that the evaluation does not change the quality of teaching given to the students.

“Hindi naman laging isinasapuso ng [professor] ‘yung comments namin as students. We can give the lowest score on the [evaluation] sheet, leave criticisms on their teaching method, and still see them going around and teaching in AB with little to no change whatsoever,” he said.

Evaluators’ anonymity

The names and sections of student evaluators are not shown in the overall results that are given by the department chairs to the teachers.

This gives the students protection from possibly being targeted by professors in class and makes the evaluation more effective as they are given the confidence to be honest in raising concerns on their professors or instructors.

However, there are cases where professors do not take the comments well and get back at their classes, questioning the evaluation result they got. But how could teachers know who wrote the comments and gave the scores if students’ identities are really kept hidden?

This has something to do with teachers’ memory retention, Placido explained. Because they know their classes, they can sometimes recall a student or a section along with an incident or something that they did which could be reflected in the students’ comments.

Laparan echoed this, saying students are really anonymous but there are hints in the comments that reveal which section they come from or who they are.

“The way they write, the way they phrase their sentences, ‘yung mga jejemon magsalita, alam ko kung sino,” he said.

This was also the case for some teachers with a few loads like Filipino professor Dr. Imelda De Castro because they are more likely to remember their students.

“Ako, I’m just handling two or three subjects, malalaman mo kung sino ‘yung estudyanteng ‘yun… Dahil inaaral mo naman, kilala mo ‘yung estudyante, papaano ‘yung style ng pagsusulat, ganiyan,” she said.

Updating the instrument

While the evaluation seeks to improve the delivery of education, some professors believe that the instrument should be updated.

Placido recommended that the questionnaire be rectified and be more specific in certain areas.

The questions in the evaluation forms should focus not on obsolete modes of teaching but also participation in community development projects and researches, as the University aspires to improve its research capacity.

The evaluation form should also include research and suitable questions adhering to the needs of the students of today’s generation as the content of the evaluation is outdated, De Castro said.

Further, the evaluation should be conducted not just once but twice—before or after the preliminary and final examinations—so the students can judge better and more fairly, she suggested.

As of now, the focus of the University is on updating the curricula, Placido said, but she is hopeful that changes in the faculty evaluation and process could be the next agenda.

“As a [chairperson], as a member of the council, we also saw that the evaluation has to be to be upgraded because, you know, iba na ang panahon ngayon,” she said.

While they believe that the faculty evaluation could use some improvements, it cannot be denied that it is a salient tool that serves the needs of the University’s foremost stakeholders: the students. F

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Vol. 54, Issue No. 3 of the Flame. View the entire issue through this link: https://issuu.com/abtheflame/docs/pages_-_the_flame_issue_3