IN TRADITION, Filipinos believe that there is life after death—an afterlife in which an individual’s identity and consciousness continue to exist even after the passing of a body. Kusina defamiliarizes Heaven as the holy realm that reveals all that is expected it would be like: a room where there is warmth and joy confined in intimate space—almost like a banquet celebrating one’s journey through life with the company of loved ones and savory dishes.

Kusina is a treat to culinary drama. It revolves around the life of Juanita (Judy Ann Santos-Agoncillo) who was born on a kitchen table. Her fate seems to be intertwined with that same room, where she discovers her devotion to cooking. The linear pace tracing from her youth to womanhood is faithful to the accustomed story-telling of a quintessential narrative. The kitchen and Juanita appear as one entity—where as she matures, the kitchen also matures. The production design is meticulously manicured as each kitchenware magically changes overtime after clever camerawork, which symbolizes the passage of time: from palayok to metal utensils, from an ice box to a refrigerator, and from tapayan (ceramic water vessel) to plastic or metal containers.

Kusina deliberately escapes the elements by which a film is considered conventional or structured. In Juanita’s house, only her fair-sized kitchen is explored. Its long-take approach might give its viewers discomfort for the camera only captures Juanita’s kitchen. However, the tale remains attached to what is outside the kitchen, and is able to tell the succession of eras through the window.

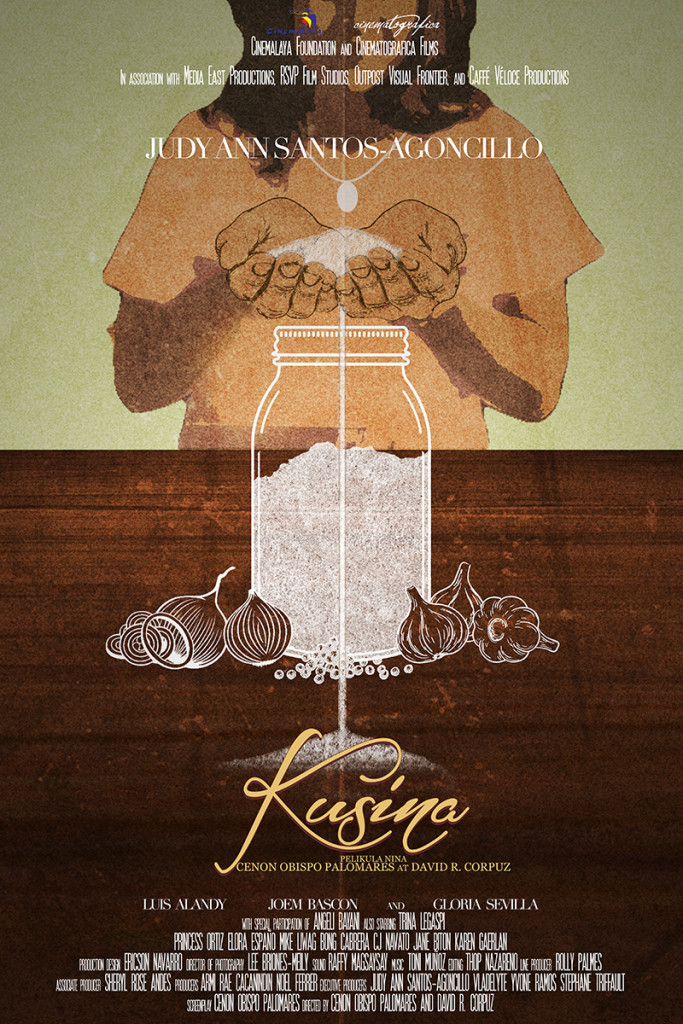

With the setting containing only one backdrop, co-directors David Corpuz and Palanca-awardee Cenon Palomares make good use of the materials they gathered, letting the core of its truth pronounce, in pleasing mumblecore fashion and the tragedy of human connection inside a Filipino household. It heavily meditates on dialogue where all that is left is piercing and powerful silence but altogether remains articulate.

The design elements are carefully detailed, coming together to be visually entrancing. The lighting is modulated enough to exhibit the appropriate mood. One of the most poignant scenes exemplifies this, in which there is a yellow spotlight focused on Juanita while she wails and writhes on the kitchen floor after receiving the news of the death of her son, Adrian (Mike Liwag). The dramatic sequences work well in contrast to being deadpan to almost everything beyond the room. This is a confident debut film, experimenting on a concept akin to a stage play.

The film is also lined with interesting characters. Inang (Gloria Sevilla), the grandmother and mentor of Juanita, follows a traditional practice of scattering rock salt—a representation of tears shed in death—in different places after the passing of a loved one. Characters are distinguished by a unique dish, as well as the color of their outfit. While Juanita wears beige, a neutral color, defining a character that is balanced and constant, her daughter, Emilia (Angeli Bayani), is beaming with sweetness in pink. The male characters are all in the shade of blue, and perhaps they all represent a wound in Juanita’s life.

In the kitchen, all the feral emotions triggered by the idea of mortality are compressed into a singularity—one thick area of pain and unease—thereby creating a physical heft that should be, or is already, familiar to most.

Kusina establishes new truths all in service of a woman and her place in a Filipino family. It is after the belief that a family is a human concept that commits to a matriarch model—a mother who places the needs of her children above all else is masterful. Most of the feelings the narrative builds are rooted in the universal denial that death is not imminent. It hurts so much because the wound fostered by the ending, while it seems for now only distant and fictional, is actually deep, and inescapable and true. In other words, the film hits where it is both most painful and most unknown. F ANDREA JAMAICA H. JACINTO