By LORRAINE C. SUAREZ

DEATH is a paradox—it is a concept known to everybody, and yet, it remains a mystery. It is something that each person is very much aware of but not something that is truly understood. Thus, one tends to observe it in a manner convenient for primal instincts: through fear and terror, emotions that are similarly observed when dealing with something in the darkness, something unknown.

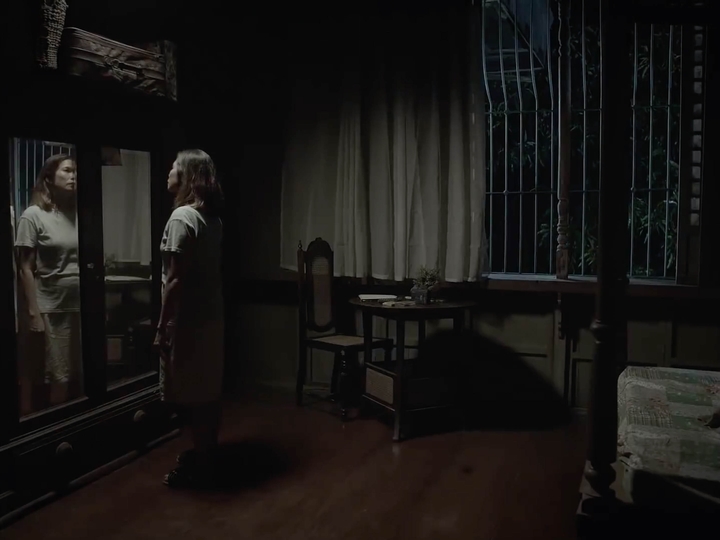

For 44-year-old Sonya (Marietta Subong), death is but a means to make a living. She is the proprietor of her family’s funeral home and the sole breadwinner in a household of two composed of an apathetic father and herself.

From the ground floor of their home, she manages their business by directing funerals entirely on her own, starting from the creation of floral pieces down to the actual process of embalming. All of this effort is done in hope of paying off the massive debt her family has incurred. Eventually, her financial troubles lead her to do some questionable acts, such as agreeing to shelter the unidentified corpse of an old woman inside her home.

The entrance of the corpse triggers a stroke of luck in the formerly hapless life of Sonya. All of a sudden, her business is flourishing once more, her previously uncaring father is beginning to talk again, and the object of her affections—a taho vendor named Elmer—is seemingly reciprocal. Things seem to have taken a better turn, and it is with glee that she welcomes this newfound fortune.

Oda sa Wala provides an introspection into the life of a lonely woman. Although alive, the titular character barely has an existence, having very little attachment to the world around her. She has neither friends nor lovers; even her last remaining family shuns her in favor of the oppressive silence in their house. Ironically, it is only with the death of someone that she receives the opportunity to be alive once again.

To the middle-aged but childlike Sonya, the arrival of the corpse is her only chance of forming a meaningful human attachment. She turns it into her primary confidant, relating to it the idle occurrences in her life as well as her deepest fears. She looks up to it as a maternal figure, a replacement for the parent that she never had, from whom she constantly seeks validation. With its companionship, she has subdued for the moment her unusual fear of the dark and her habit of biting her fingernails in anxiety. With its guidance, she is able to journey toward discovering her worth as a person.

Throughout the film, Sonya’s character develops in subtle shifts. While this may be seen by others as a drag to the pacing of the story, this slow evolution is what fully fleshes out the protagonist. Through the angles of the camera, her likeness is portrayed in zoomed-out sceneries and side views colored by a dull and dreary aesthetic that eventually transforms into a more vibrant and brighter one in later sequences. The color scheme is also reflected in Sonya’s outfits in her transition from ‘plain Jane’ get-ups to feminine blouses and airy skirts.

What ultimately makes this entry unique, however, is its heavy use of silence. It depends on neither music nor sound to build up its scenes. Only one song is ever used and even then, it appears only in a few select scenes. The film’s reliance on silence means that it effectively captures the monotony and dullness of Sonya’s daily routine. These, in combination with the various camera angles, make the film slow-paced but not boring.

Overall, Dwein Baltazar’s entry to the QCinema film festival delves into the unknown by capturing the hidden fears that lurk within the hearts of many. It confronts the morbid realities that are known to all—such as loneliness and death—holding testament to the fact that a corpse can have more of an existence than an actual living person. F