WHEN THE only way to move forward is to look through the past no matter how painful it was—how does one brave through this place of memory without feeling displaced?

Located at a point where stretched waves meet the shore, Kono Basho (This Place) coasts through Rikuzentakata City to tell the story of two sisters torn apart by family complexities and whose hearts seem to be on opposite sides of the same coin.

As one of the full-length entries for the 20th Cinemalaya Film Festival which ran from Aug. 2 to 11 at select Ayala Malls Cinemas, Kono Basho garnered multiple awards, most notably the Best Director Award for University of Santo Tomas alumnus Jaime Pacena II. The film also won the Best Production Design Award, Best Cinematography Award and Best Actress Awards for Eero Yves Francisco, Dan Villegas and Gabby Padilla, respectively.

The film starts with montages of Rikuzentakata, a city still recovering from the 2011 tsunami, accompanied by narrations central to the film’s themes of shared grief and healing. In this coastal city located in the Iwata Prefecture, Ella (Gabby Padilla) pays a visit to her estranged father’s funeral in an attempt to give herself closure. There, she meets her late father’s Japanese wife and daughter.

Though her presence was welcomed Ella was confounded with wrongfulness and grief, especially toward her half-sister Reina (Arisa Nakano). Throughout the film, both Ella and Reina navigate the grief from their father’s death and their differences despite being connected by blood and personal issues.

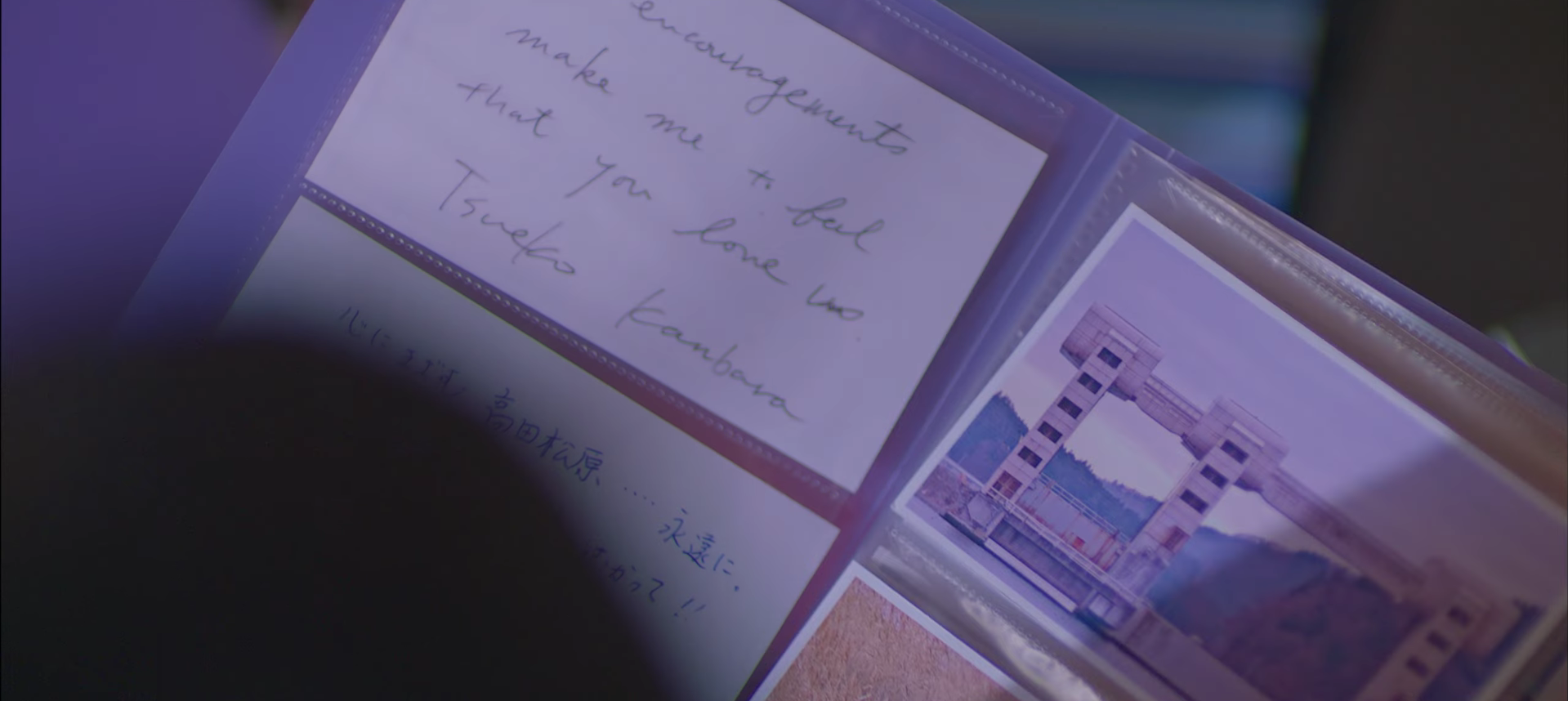

The film constantly connects their relationship and the city of Rikuzentakata, paralleling their strained relationship to the tsunami tragedy. Despite the city no longer being the same as before, the residents of Rikuzentakata continue to move forward, rebuilding their lives through images of the past despite the pain it reminds them of. This is reflected in Ella and Reina’s relationship across the film, accompanied yet again by montages both of the city and their father’s memory.

The film showed that both Rikuzentaka and the two sisters are in the process of recovery, but went on to say that healing is not linear. However, continuously moving forward with an open heart and mind is pivotal in doing so, and one can only accomplish this by thinking of the past as a guide rather than a disruption.

From the beginning up until the end, the film remained faithful to its central theme of healing. It focused on a loved one’s death while incorporating other elements such as differing coping mechanisms, personal struggles and the strength in having support systems.

Its most applaudable aspect was its added intimacy. Aside from the theme, the technical aspects and how it was executed made this film much more personal than it already was.

Whenever montages flashed in the film, these were always supported with a low and soft background music. But the actual scenes relied more on the raw sounds of the characters’ movements. Most of it were quiet sounds from their movements and any sound from the outside world, such as the creaks from wooden floors, was not heard. Though not as noticeable, it was a good addition to the vulnerability of the film, as it enhanced the already visible isolation around the main characters.

Kono Basho’s cinematography allowed the audience to feel closer to the world-building of the film. Rather than always aiming for stable and balanced angles, there were instances where the hand-held movement, emphasising the intimacy of the scene.

This can be seen in the scene where Ella and Reina stand side by side at the Memorial Park. The camera focused on the two of them walking backwards with less stability. The technique of zooming in on characters, used during a scene where characters were walking away, contributed to the film’s sentimental characteristic.

Another feature that may not be too noticeable was how the film was presented in exposure, even in moments of negative feelings. There was a lightness to it—not blinding, but more of a soft radiance. This subtle use of light enhanced the emotional depth of the film and the atmosphere, enhancing the theme of healing during moments of negativity.

The only flaw was its rather incomplete storyline. While its incomplete storyline also pushed viewers to become more receptive and to seek context clues, providing more background to the story would have been essential. The lack of background made some information hard to absorb. Though this was just a minimal flaw and did not largely affect the film.

Overall, Kono Basho delivered personal sorrows straight from the screen to the audience with impactful yet subtle performances and directing. The film’s showcase of similarities between the recovering city of Rikuzentakata and the fragmented relationship of the sisters are poignant reminders to everyone that healing is not linear and every person has a story they hide and a story to tell. F