THROUGH WHAT I know of Theo van Gogh and how he supported his brother Vincent in both the artist’s troubles and artistic endeavors, I always end up seeing my brother Carl in him. He is much the same as Theo: both knew what to do to keep their brother going.

By saying that he is very much like Theo, I do not mean to say that I am very much like Vincent. There are not that many things I have in common with the famed artist. In fact, I can only think of four.

Two of the things I have in similarity with the ill, tortured, genius painter Vincent van Gogh is that I am ill and tortured. Quite unfortunate. Had I been a genius, perhaps I could forgive the heavens for letting me be tortured.

The third similarity is our pursuit of an artistic life. But the fourth, and most important similarity is that I, too, have a supportive brother. Brothers, in fact—and a sister, too (I am the youngest of six). My mom and dad appreciated my writing as well. They all expressed support for my writing in their own ways.

This is not to claim that I do not appreciate any of my other siblings’ support. But there lies a distinction.

Like Theo, it is Carl who understood my illness the best. He knew that it was not simply for madness’ sake, but that I am afflicted with an illness and that I am in pain and in need of help.

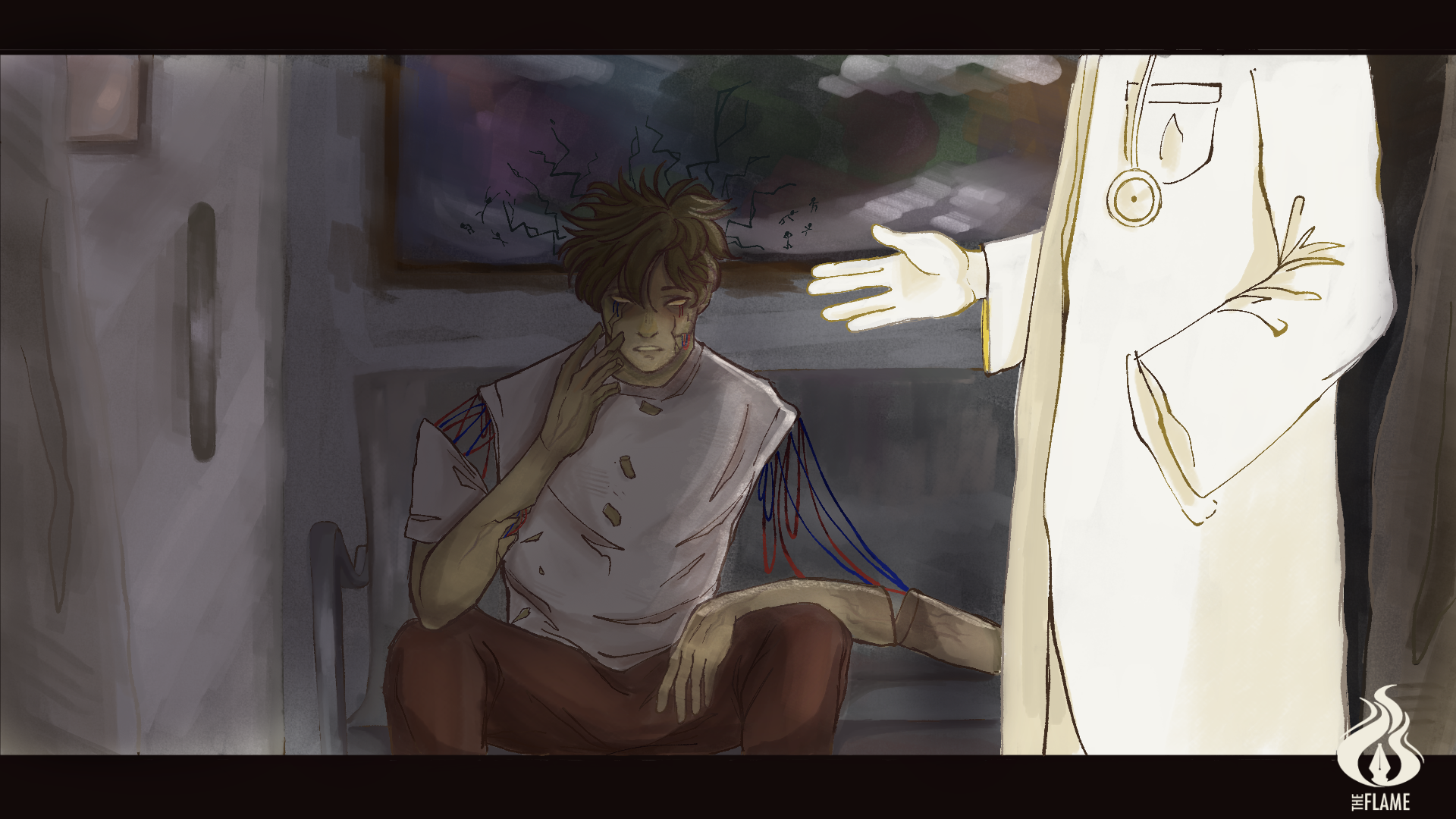

Like van Gogh, I have an illness, too. When I was first clinically diagnosed, it was because my brother referred me to a psychiatrist he knew—someone who mentored him when he was in medical school. It was like what Theo did when he sought for a doctor who could help his brother.

And my treatment would have continued, if not for the pandemic that started no more than a month or two after I was diagnosed. It was then, in isolation, that I started suffering from a series of mental breakdowns.

It must have been hard for my family to understand. They tried to help, of course. But they must have been accustomed to having their guards always drawn up, that when I was crumbling with no shields up, as if naked without armor, they really did not know what to do.

When you are beaten down, it is as if you know there is something you need to feel better, but somehow, you find yourself incapable of naming it.

I did not know what to name my needs—or how to name it. They did not know either. But my brother did.

He and my mother presented me with a chance at solitude and gave me a space in his three-bedroom apartment in Dagupan. He occupied the other room and he left me to my own devices.

And the magic in it was that he somehow made me feel that should I need any help, all I had to do was knock.

It was like I had a personal asylum.

This reminds me of the time Vincent checked himself in a real asylum after he suffered from a mental breakdown. Just a few months ago, I almost did, too.

I asked my brother if he knew any asylum where I could spend some time to get better and preferably one where I could still write. He recommended some, but none fit what I felt I needed at that time.

Asylums do not allow any objects that could feasibly harm any of the patients. A typewriter, pen, or a laptop would be out of the question. I ended up not going and decided to find a good alternative: go back home and make that my asylum.

Surprisingly, I felt my family change for me. They gave me my own room, did their best not to disturb me, and would ask me if I wanted to go out or do anything that they thought would benefit my mental health. It was as if they had become, in many ways, like Carl.

When I was there two months ago, I was able to write again. On many occasions, writing saved me from death. My brother knows this, and he has always been supportive of my writing. It was he who funded my first self-published short story collection. Even now as I get closer to finishing my new novel, he is open to the idea of helping me fund it.

Theo used to do that to Vincent, too. He funded Vincent’s passion, helped his brother’s name be known in the art community, and connected him with several artists. He knew art was, in many ways, saving his brother. It was art that gave Vincent’s days great meaning.

My art saved me too, and if it were not for my brother’s help, I would have thought of myself as a failure. My writing career would not have begun and I would end up sleeping scared under the shadow of my failures.

I suppose much of this comparison stems from the fact that I empathize deeply with Vincent’s struggle. It was through his art where he could at least tell himself that despite how dark some days might get, beauty still exists in the world, and it would be a waste not to appreciate it.

We will die eventually; that is part of our contract with life. But if I die before my brother, he and my dream will sit next to each other at my funeral. For the only reason that my dream will not come with me to the afterlife is because my brother saved it much like he would a patient—with support, care, and a genuine interest to save him.

Should I turn my brother’s effort into a phrase, it would be this: let the weight shift unto my shoulder ever so slightly so that you can be freer to write and not feel that you are burdening me.

I am not burdened anymore, brother. But if there comes a time that it is you who is burdened, and I have the strength and means to carry it, I will. F – Noe Murcielago