THE SPREAD of misinformation and disinformation caused bigger challenges for journalists covering the pandemic, journalism professors’ study revealed.

The research titled “Reporting in the ‘New Normal:’ How the COVID-19 pandemic affected journalistic practices in the Philippines” by veteran journalists and UST journalism educators Felipe Salvosa II and Christian Esguerra found that newsrooms paid more attention to bringing accurate information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We saw a pattern of newsrooms allocating more resources: that includes manpower and also time to handling or dealing with misinformation and disinformation,” Salvosa said in an online research presentation held on August 31.

Because of this, a significant level of distrust was formed among journalists, the researchers said.

They added that even if the information came from reliable sources, journalists still intensively cross-checked and fact-checked information, prompting them to work longer hours.

“We got the impression that journalists are trying to consume as many information as they could while validating those information with other sources,” Esguerra said.

“They are trying to check whether this source is trying to do some cleaning for the government or if this source is to unnecessarily attack the government position or policy,” he added.

Fears of virtual reporting

The sudden shift to work-from-home set-up also became a problem for many journalists. Aside from blurring the line between their personal and work time, they also developed a “fear of failure” when delivering information.

“Working alone at home, away from colleagues and connected only via messaging apps, was also taxing for many of them,” Esguerra added.

The fear came after they realized that additional sources of information for validating the acquired information were limited.

“Because [the journalists] had limited access to information, they worry that they too are instrumental in spreading inaccurate information knowing that this will have a direct effect on the public,” Esguerra said.

This resulted in adopting several mechanisms that would ensure the information is accurate and in “proper context” like the “vertical and horizontal verification.”

“Journalists found it imperative to check official pronouncements against official or field data, and validate further using international data,” Salvosa explained.

“[They] really tried their best not to sacrifice standards. The very fact that they developed these verification routines is an effort that reporting standards do not suffer because of the pandemic,” he added.

Meanwhile, Philippine Daily Inquirer reporter Julia Alipala agreed that there is “fear” in reporting during the online set-up.

“Our fear that time was everything is done virtually. How can we frame a news story if newsrooms in Manila and even outside the country get the same information? We have to go down. We have to get our own stories from the people and let them speak about their situation,” Alipala said.

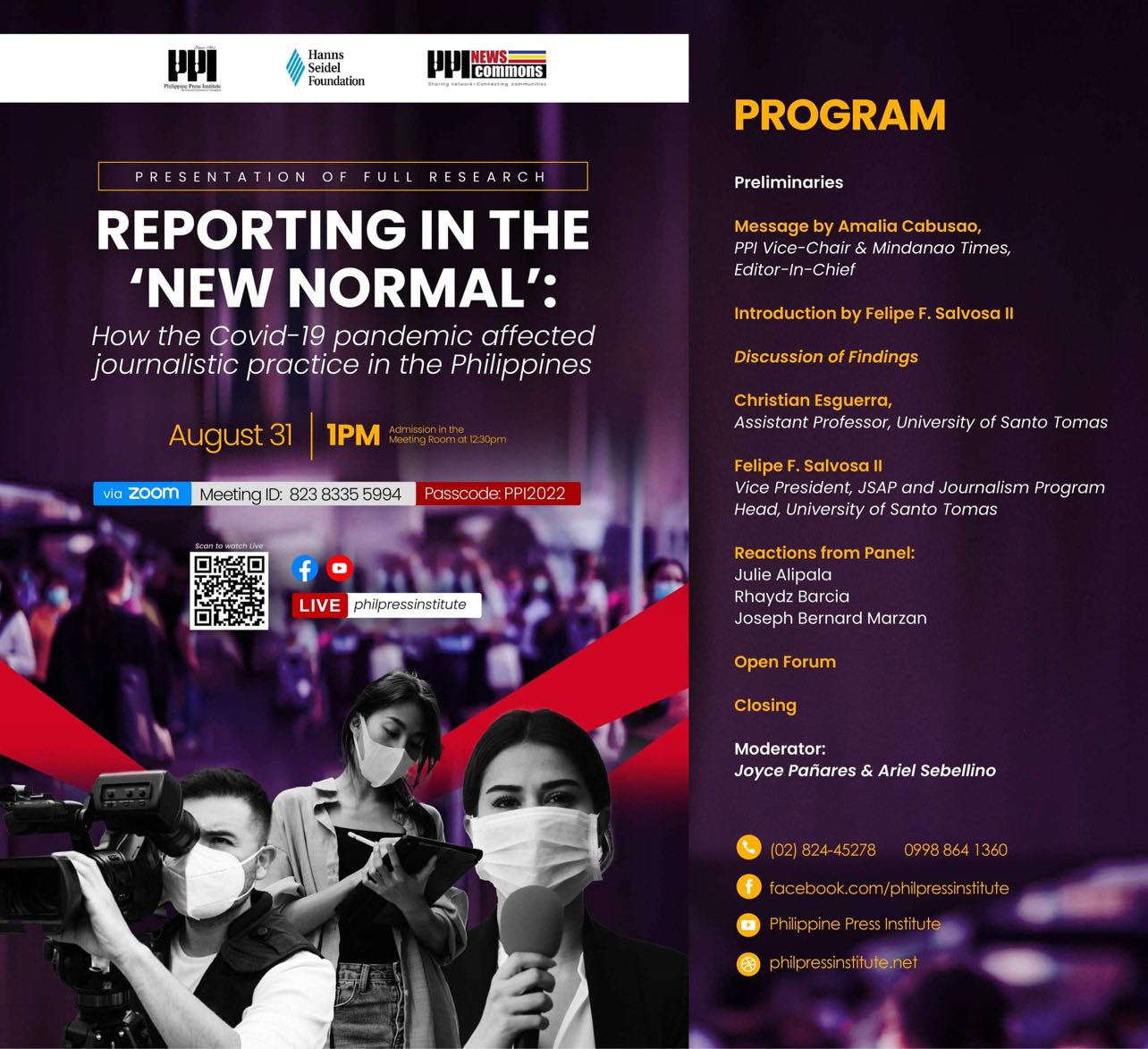

This research was presented during a research forum organized by the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), Hanns Seidel Foundation, and PPI News Commons held via Zoom. F – R. A. Figueroa with reports from Aubrey Shane Lim