by EUGENE LORENZO

THERE SEEMS to be no place now for the old in Manila. Consider the University Belt: high-rise condominiums sprout at a dizzying pace, and many of the houses that once belonged to a gentler time meet the fate of decay, destruction, and oblivion. This seems to be the case with the city’s vanishing old districts today.

But as in old-timers who lend wisdom to their households, the buildings of old Manila lend wisdom and memory to the city and its present inhabitants. Believe it or not, there is one at the heart of the U-Belt that is unbelievably intact, as if it were caught in amber.

Beyond the U-Belt’s asphalt roads flanked with dusty commercial establishments, fetid garbage piles, and cramped jeepneys, behind a thicket in a lot between Morayta and Recto, just a few blocks away from España Boulevard, stands a living edifice that persists to preserve a noble cause from the world of yesterday. It proudly declares its name in front: Gota de Leche.

Entering the site

The Gota de Leche Building has not lost a speck of its charm, despite being more than a century old. Even the unaware passerby would notice the dignified air that this old building wears, a far cry from the shabbiness that is commonplace in the area. Its façade, clad in pink, has a certain proportion that is reminiscent of old cities in Europe. Arches and columns line an open arcade on the building’s right, which faces a front garden canopied by trees.

A curious detail that one notices are the babies and mothers ornamenting the whole place. The fountain, the reliefs, even the capitals of the columns—all follow a theme that speaks of the building’s storied heritage.

Designed by Arcadio Arellano with the assistance of his brother Juan (both famed architects in prewar Philippines), the structure was patterned after an iconic edifice from the Italian Renaissance: the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents) by Filippo Brunelleschi, located in Florence, Italy.

Finished in 1915, its purpose is to house La Protección de la Infancia, the country’s first charitable institution dedicated to maintaining the welfare of mothers and children. The foundation still lives and operates today in that very building.

It is the site of a long and continuing history, one that is replete with hardships that reflected the struggles of the nation, and with strong-willed personages who worked to solve them.

Pioneering the fight

The early years of the twentieth century was a terrible time to be born as a Filipino. While Filipinos were still reeling from the aftermath of the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War, another fatal problem was harming the populace.

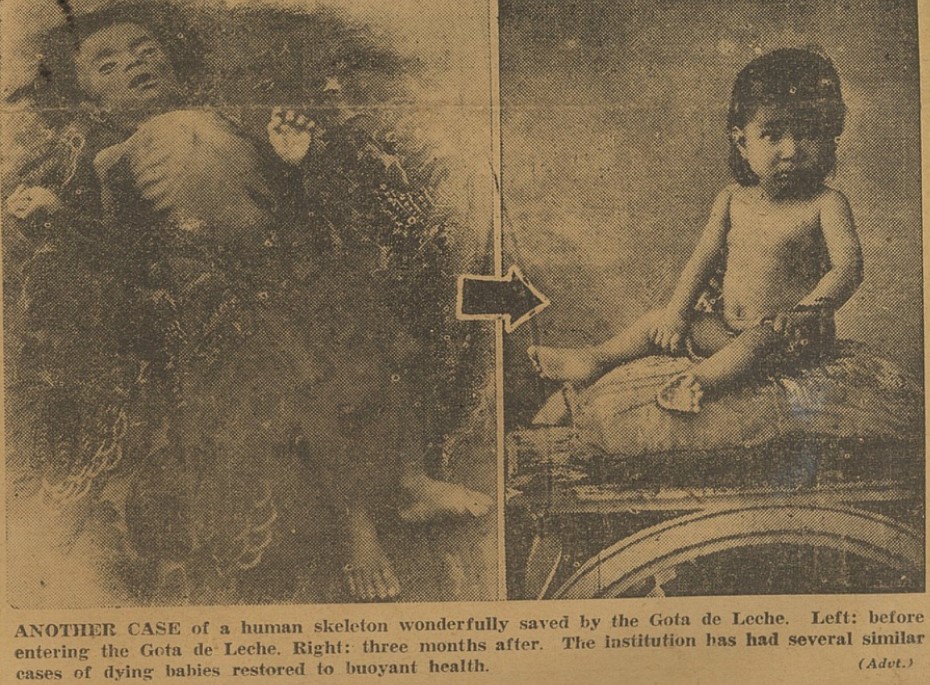

Infant mortality in the country was among the highest in the world. According to historical records, hundreds of Filipino children were dying before reaching the age of one. Only 4 out of 10 newborns would live. This was the effect of a disease called beriberi, which is caused by the lack of vitamin B1. As malnutrition riddled mothers during wartime and the succeeding years, the nation’s new generation was bereft of the nutrients necessary to its survival.

At the turn of the century, Filipino doctors were already looking for ways to solve this problem. It was also at this time when, radicalized by ideologies, Filipino women were starting to publicly campaign for their rights.

In 1905, Concepción Felix de Calderon, a working-class woman, gathered some independent, educated, and patriotic Filipino women, and established the first feminist organization in the Philippines—the Asociación Feminista Filipina.

Inevitably, the first feminists took on the fight against the high rate of infant mortality. In 1906, members of the feminist group, along with a handful of male physicians, met in a house in Quiapo to discuss the establishment of a station that would provide pasteurized cow’s milk to babies. They also sought to educate mothers on hygiene and nutrition. Present were the doctors Manuel Guerrero and Joaquin Quintos, both of whom were then leading the research on beriberi, and eventually became the founders of its cure (commonly known today as tiki-tiki).

La Protección de la Infancia (The Protection of Children) was incorporated on February 15, 1907, establishing its place as the first citizen-led NGO of the country. Calderon was at the helm—then a progressive decision, considering the patriarchal culture of that era.

Its first board members included the most illustrious members of Filipino society: Trinidad Rizal (sister of José Rizal), Librada Avelino (founder of Centro Escolar University), and Dr. Fernando Calderon (first Filipino director of the Philippine General Hospital), among others. Its by-laws were written by no less than Felipe Calderon (author of the Malolos Constitution).

Gota de Leche (Drop of Milk), its milk station and health center, officially started its operations on October 17, 1907. It has never ceased since.

Anna Leah Sarabia, writer, feminist, and the present managing executive of La Protección de la Infancia, said that the establishment of Gota de Leche was a progressive move from the first feminists.

“If you look at the history of the Asociación Feminista Filipina, it included not just [fighting for] education and protecting women prisoners, but also educating women in hygiene,” Sarabia told The Flame.

“When you talk about hygiene, I think it implies a lot of things that had no names,” she said. “For instance, family planning, contraception, understanding of the menstrual cycle, understanding of the birth cycle—there was no information for them, and there were no words for them. And so, it was quite logical for the feminists to be the ones to establish La Protección de la Infancia.”

Despite facing challenges in securing funds, the Gota de Leche members persisted in upholding their cause, exhausting all means to keep it afloat. Their efforts proved successful.

Nearly all of the thousand infant beneficiaries enrolled in their program, most of whom were of poor background, grew into healthy adults.

More puericulture centers were founded throughout the country, reducing infant mortality from 50% in 1905 to less than 20% in the 1930s.

Due to its success, Gota de Leche eventually transferred to its present location in Sergio H. Loyola Street. It was then a lone building in the sprawling fields of old Sampaloc—12 years older than the University’s Main Building, 24 years older than the oldest building on the FEU campus.

Defying the war

The gentle temper of prewar Manila eroded when the Second World War came. December 8, 1941 was the terrible day that commenced the years of agony, despair, and carnage for Filipinos.

Yet during the three-year Japanese Occupation, the Gota de Leche was a veritable safe haven in the city under siege. This was thanks to yet another strong-willed woman, who also happened to be the first woman to practice law in the Philippines.

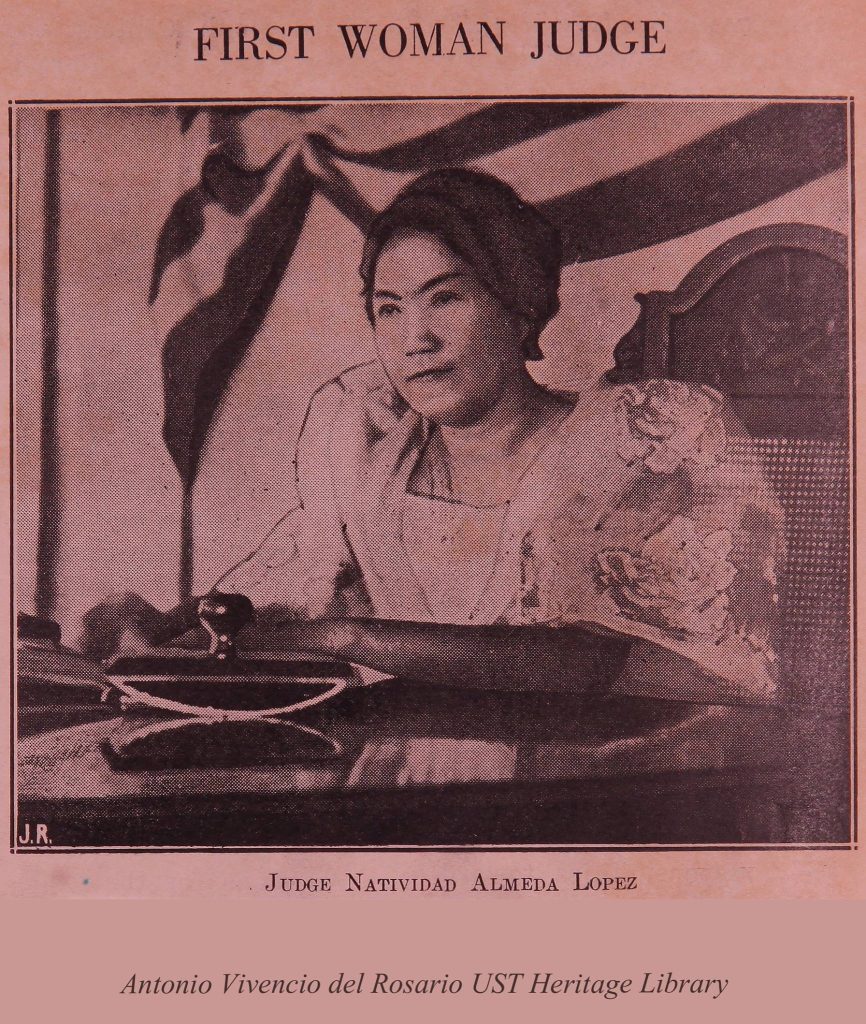

Natividad Almeda-Lopez (1892-1977), at 15, was already attending those early meetings as a member of La Protección de la Infancia. She eventually served as the president of the foundation in 1936, balancing her work as the city judge of Manila—making her the first woman judge in the Philippines—and as a major proponent of woman suffrage.

Sarabia, who is the eldest granddaughter of Justice Natividad, remembers being taken by her grandmother to fund-raising operas and programs as a child. She admitted that growing up, she did not appreciate the charitable work her grandmother was doing.

“When I had my own NGO in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I could not understand why my lola and then later on my mother were so dedicated to Gota de Leche, because I found it so old-fashioned,” Sarabia said. “Because for us, if you want to help the poor, you get them organized. But then, later, I started to do my own research. That’s when I found out that in fact, all of us women owe a lot to Gota de Leche.”

Gota de Leche was under the helm of Justice Natividad when war broke out. Amid the Japanese Occupation, its operations went uninterrupted, even delivering daily rations of milk to the babies of prisoners of war in the UST Internment Camp.

How was this possible, considering how the Japanese seized the buildings that surrounded it? How was Gota de Leche not bombed when, come to think of it, almost all of its surroundings were either scarred by shrapnel or reduced to rubble?

Sarabia asked these questions to her mother, Lourdes Sarabia, who was the daughter of Justice Natividad. She disclosed that according to her mother Lourdes, Justice Natividad bravely demanded two things from the Japanese, who asked her to continue working in the government in the interest of making the Occupation appear normal for Filipinos.

“She made a conditional agreement—and this is what my mother said—that she would agree to continue working as a judge, on the condition that the Japanese soldiers don’t interfere in her cases or in her judgement. The second was that they will allow Gota de Leche to do its work without any interference,” Sarabia said.

“That’s what happened. Gota de Leche was untouched,” she said.

Because it stood unharmed amid the utter destruction of the city after the Battle of Manila in 1945, it was used as an office for war damage compensation in subsequent years.

Restoring the glory

The postwar years that followed proved even more challenging for the foundation. As the country picked itself up from the ruins, Gota de Leche resorted to ingenious ways to generate funding.

Sarabia said that during Martial Law, the funds that came from the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office–of which Gota de Leche was an original beneficiary–were halted when the law was amended by the Marcos dictatorship.

Because of this, Gota de Leche had to open its place for rent. A school had taken over the place; plywood boards were installed erratically to divide the place into rooms. The environment of Gota de Leche also changed, becoming helplessly congested as the tides of rapid urbanization washed over Manila.

No longer was the Gota de Leche the building that it had been for decades.

Thus, in 1999, the late Lourdes Sarabia, then the director of the foundation, took up the challenge of restoring it to its former glory. With the project spearheaded by architect Augusto Villalón of the Heritage Conservation Society, Gota de Leche underwent a complete restoration.

It was finished in 2003, and was awarded Honorable Mention by the UNESCO Asia Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation. It was also declared as an Important Cultural Property by the National Museum of the Philippines in 2014.

Preserving the heritage of care

Today, the Gota de Leche remains steadfast in fulfilling its original mission. For Sarabia, although the problem of infant mortality has improved, malnutrition and stunting remain urgent problems for Filipinos. According to a UNICEF study, 95 Filipino children die from malnutrition every day.

She added that government provisions for maternal health remain inept due to corruption and conservatism. “It’s like we’re back in a war situation,” she said.

At present, Gota de Leche attends to more than 150 beneficiaries. Apart from providing milk for disabled and malnourished children, and nutritional support for pregnant and lactating mothers, the foundation also extends relief support to disaster-stricken areas.

They have also added in their programs the conservation of the heritage building.

The latest hardship that the foundation grappled with is the COVID-19 pandemic, when they nearly closed due to the dearth of income, which was generated mainly by the parking services they give. And yet, as it had repeatedly done throughout its history, Gota de Leche persisted.

When asked which moments proved the most challenging for her, Sarabia laughed and said, “There are no challenging times—every day is a challenge! Every day you look for ways to make it survive.”

Indeed, it had been defying famine, wars, disasters, and now a pandemic, for more than a century. Gota de Leche still nurtures poor mothers and children, 117 years after it was founded, and it continues to be a source of hope in times of uncertainty.

The statues of healthy babies cradled in the arms of their mothers, the charming old building standing defiantly in the city, the foundation and its kindness–all of these affirm an assurance in an unforeseeable future. For as long as the heritage of Gota de Leche lives, there is hope for the generations of tomorrow. F