by JOHN PATRICK A. MAGNO RANARA

A DEEP, heavenly version of Lucio San Pedro’s Sa Ugoy ng Duyan plays in the background, soothing and serenading visitors who enter the newly-launched 360-degree virtual exhibit of the National Museum of the Philippines. The museum commemorates the return of 115 art pieces brought to New York City more than 40 years ago.

Installed at the National Museum of Fine Arts, The Philippine Center New York Core Collection of 1974: A Homecoming Exhibition transcends distance and boundaries. It celebrates the power of local artistry, encouraging it to go beyond its roots and represent the Filipino identity to the rest of the world. The exhibit showcases modern and contemporary art that emphasizes folk aesthetics and the indigenization of Western art styles.

The Philippine Center in New York was first established on May 10, 1973 before being inaugurated a year later on Nov. 14. With a commitment to nurturing Philippine culture, promote tourism, and enhance the diverse and colorful image of the country, the center displayed a collection of 120 artworks by 52 artists.

And now, after 47 years, 115 of these artworks have come home to their roots, making it possible for the younger generation to see and appreciate these historical works that have represented their identity. The following historical works give just a glimpse of the Philippines’ rich culture:

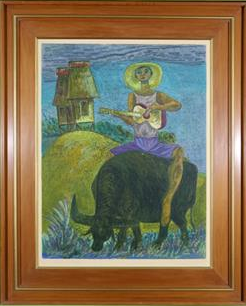

Serenade by Manuel Rodriguez Sr.

Made through the art style of etching, Rodriguez interprets an image of a young man riding a carabao, breezily playing on the strings of his guitar as he sings his song through the night.

Etching is a printmaking process that requires etching needles to carve lines on metal plates. Acid is then poured over the plates, creating recesses that can retain ink. After filling the lines with ink, the plate is then pressed onto paper, and the image is transcribed onto the material.

In the olden days, it is common to hear tunes of romance filling the evening air as men would sing sweet and gentle serenades to their lovers sitting by the window. However, in Rodriguez’s work, it can be seen that there is no maiden to be wooed by the young man’s music. This may signify that the serenade is meant to thank the faithful carabao accompanying him.

Serenades are mostly sung to a lover, a friend, or a respected person, but the animals that roam the earth should also be offered respect, especially the Philippines’ beloved giants who are loyal partners to hardworking farmers.

Basket Weaver by Norma Belleza

Muddy splotches of oil paint form the image of a basket weaver, one of the widest and oldest craftsmen in many Asian civilizations.

Conceived from the mind that has consistently portrayed women in all their daily burdens, the smeared and seemingly sloppy strokes of Belleza’s painting depict the weariness of a woman weaver as she constructs her complex craft of grass or wooden material.

Basket weavers are still very much prevalent in remote villages and communities, such as that of the Tagbanwa tribe from Coron Island. For the easily captivated tourist, handwoven products often serve as souvenirs from their distant travels. In the tired eyes and burdened backs of the weavers, however, not only does it serve as a remnant of their cultural identity and deep-rooted heritage, but it is also a means to keep their family and their community alive and thriving.

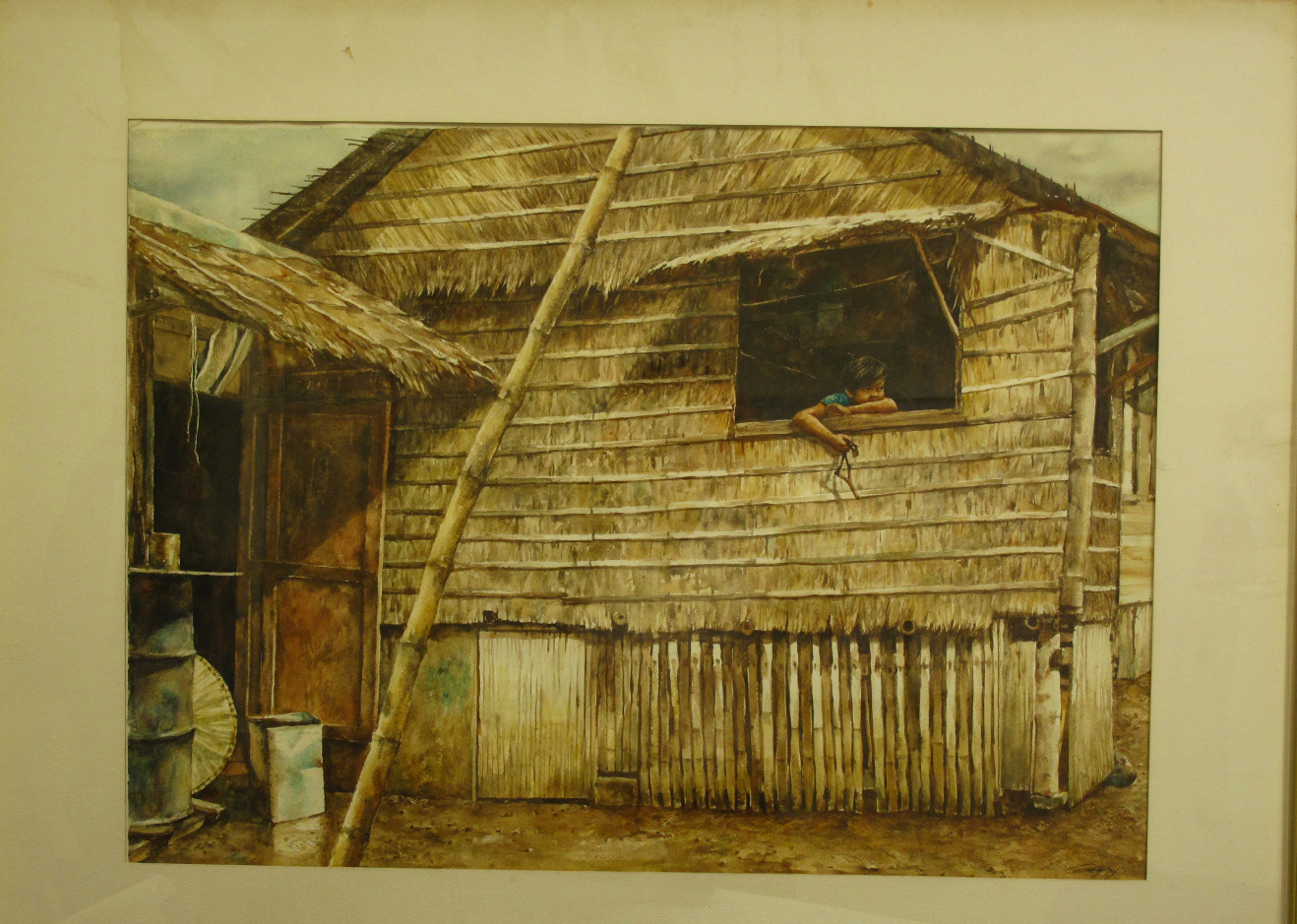

Day Dream by Agustin Goy

Through his hyper-realistic watercolor painting of a young boy staring outside the window of his humble, provincial home, Goy fills viewers with a sense of repose and longing; of tranquility and the aimless musings of the mysterious mind.

Goy expertly and meticulously captures the ambiance of a hot and lazy afternoon through the earthy brown hues and shadows of the nipa hut, and even the soiliness of the ground below. Much like the young boy, viewers may feel themselves staring absentmindedly at the humid portrait as they are enveloped with peaceful isolation.

With the COVID-19 pandemic still overstaying its welcome, daydreams have become a habitual experience for Filipinos craving to go out under the sun, free from the restrictive chains of face masks and safety protocols. But the maddening isolation has also paved a way for reflection and self-healing.

Music, artistic crafts, and the wondrously boundless imagination—The Philippine Center New York Core Collection of 1974 paved a way for visitors to rediscover age-old artworks. More importantly, it has also opened opportunities for them to be inspired with new ways to adapt to the changing environment and find their own temporary paradise. F

This article is originally published in The Flame’s third issue. Click here to read.