THE UST Museum of Arts and Sciences has been home to some of the greatest cultural treasures of the country, ranging from paintings, sculptures, and other artifacts.

Since opening its doors in 1869, the museum witnessed the evolution of times and mirrored Filipino values through various generations.

Its current assistant director John Carlo Sayco shared with The Flame some of its treasures that are often overlooked by visitors but are great contributors to the representation of Philippine history and the Filipino-Thomasian identity.

Fernando Amorsolo’s “Bayanihan” (1959)

The Hall of Visual Arts is introduced with a breath-taker: Fernando Amorsolo’s “Bayanihan” painting. It features a group of men trudging uphill carrying a bahay-kubo. They are led by a man with a woman bearing an infant in her arms beside him.

There is a delicate kind of grace in the scene—a glowing sky with the lambent sunlight trembling in the landscape.

Rendered in a mastery that has put Amorsolo among the greats, the painting captures the Filipino culture of care and community. Sayco described, “What better way to open up a gallery than by showing one of your (Filipino) values.”

Aside from this gong-striking prelude, the gallery also houses a narrative on the development of painting in the Philippines, with about 500 artworks, ranging from the 17th to the mid-20th century. On display are religious paintings from 400 years ago by Spanish artists and early local artisans who copied them.

These paintings were once originally hung at the UST Intramuros campus and survived several catastrophes, including the earthquake of August 20, 1937. Through the transfer of the collections to the present Sampaloc campus in the late 1930s, the works were spared from the total bombardment of Manila during the Second World War.

The visual arts gallery, formally established in 1940, has since expanded its collection, affirming its place as one of the nation’s foremost art institutions. At present, the gallery houses a great number of works by masters who shaped Philippine art and culture.

Viewers can see other paintings, namely works by ilustrados Juan Luna and Felix Resurrección Hidalgo, and the portraits and rural landscapes by maestros Fabian Dela Rosa and Amorsolo.

The collection is also rich with Filipino modernists—an abundance attributable to the ties of the movement’s pioneering triumvirate of Victorio Edades, Carlos “Botong” Francisco, and Galo Ocampo with the University.

St. Thomas Aquinas image

Upon entering the hall of Philippine religious images, there is a bit of an unease. One might find the array of icons present in the room a bit intimidating, perhaps due to the exemplary lives of those represented by the sculptures or the way they stare back at their beholders.

As Sayco put these into words: “Some people may find it scary, but I tend to find it otherwise.” Indeed, after letting one’s guard down, one may appreciate the Filipino artistry in the santos.

The Philippine religious images collection includes rare crucifixes made of ivory (the world’s second-largest ivory crucifix is also being housed in the museum), reliefs of Biblical scenes, and statues of saints. It presents ecclesiastical art as legacies of the Filipino’s deep relationship with faith and devotion.

“This is part of our heritage. Meaning to say, [this is handed down from generations before us,] that had significance in the past, that exists until the present, and can be appreciated by future generations,” Sayco said.

But above all, a sculpture of St. Thomas Aquinas, a familiar sight for Thomasians, can be found at the end of the hall. He is identified by the large golden emblem of the sun, which ornaments his chest.

There is also the quill on his left hand, the book and church replica on his right, which symbolizes his huge contribution to Theology, and the dove that hovers above his ear. These are the attributes of the saint after whom the University is named.

Every 28th of January, this image—resplendent in its intricate detail—is brought out from its glass case and paraded around the campus in a procession on his feast day.

As the University’s patron, St. Thomas Aquinas is a model for students “to look up to, and try to emulate in being a student of life,” Sayco said.

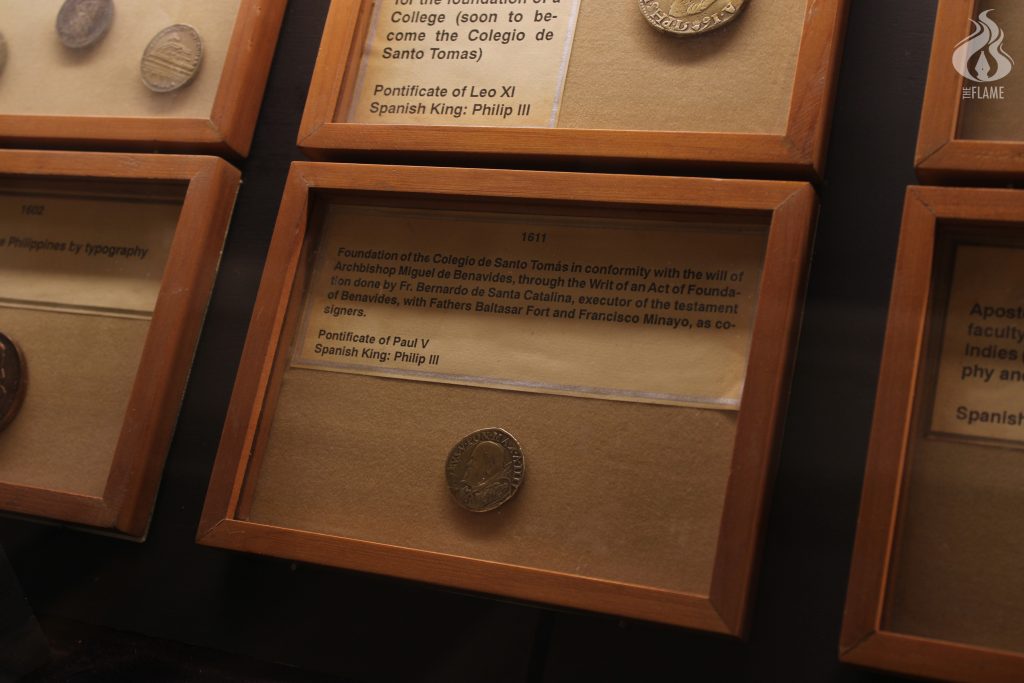

Coins and medals

Like the images above, these objects also build what Filipino and Thomasian heritage is. A section at the center of the museum’s mezzanine, which houses several memorabilia from the 1600s, tells a narration of the formation of the Thomasian identity.

For instance, staring at a coin from 1611, when the UST was founded, gives Thomasians a sense of belonging in the University’s long and continuing history.

The coin is part of the coins and medals collection, displayed in table cases among other antique coins minted to commemorate University and world events, including the medals awarded to some notable persons, from University professors to Philippine presidents.

Ceremonial maces

Aside from these coins and medals, the display also has a tall cabinet containing more heirlooms of the University. The centerpiece–a pair of ceremonial maces shining in fine silver–towers over the entire museum.

Carried before the rector to symbolize his authority, it is the pair that has opened graduation processions (done on horseback in the streets of Intramuros) and inaugurations of academic years since the 17th century. It is also the same pair gracing University events today.

Moreover, surrounding the maces are objects that witnessed the lives of past Thomasians. Present Thomasians may be surprised to find themselves relating to the objects, for certain university traditions are still alive today. For instance, the 25-minute sandglass that timed doctoral candidates’ defenses for centuries is the same 25 minutes that frighten today’s thesis defenders.

“These things exist even before, and other practices that are existing up to now can be reinforced by collections such as this,” Sayco said.

It is no coincidence that the memorabilia cabinet is placed at the museum’s center, like a dignified mansion overlooking a village. It was a deliberate choice, Sayco explained, to embody the museum’s role as “the leader in giving witness and preserving the heritage of our University.”

Chinese wares and an Ifugao house

At the left side of the museum hall are wares of different persuasions sitting in glass vitrines. This is the ceramics collection which offers an abundance of treasures from several regions in Asia. It covers a period from the 11th to the 19th century.

Among the collection are ceramic wares from China—where the art of ceramics is developed. Some Chinese wares, estimated to date from the early 14th century, were found in the Santa Ana excavation site in Manila. Long before colonization, the echoes of ancient trade routes and merchants resonate in these artifacts.

On the other side of the hall is a stretch of ethnographic items sampling the diversity of Filipino identity.

An interesting object is the miniature model of an Ifugao house. One notes that the structure is elevated in tall wooden posts with cylinders atop them.

Sayco explained that this feature functions for security: to keep the rats and thieves away. He added that the thickly thatched grass roof insulates its inhabitants from the cold.

Designed and perfected by the natives with their needs and the environment in mind, Sayco said that the Ifugao house is a feat of indigenous wisdom, a tangible symbol of Filipino cultural heritage.

The astute viewer may, however, notice that some of the descriptions in these collections need more precise information. This issue was pointed out on Twitter by a museum visitor last September, who called out an error in a certain shield’s description.

This is a problem that the museum administration acknowledges. “We have yet to find experts to identify much of our collection,” Sayco said.

Despite this, they see it as an opportunity to improve the museum. “The museum welcomes corrections,” he said, speaking on the Twitter matter.

“And up to now, [after a brief correspondence,] we’re waiting for the response of the group who pointed it out, because we’re trying to collaborate with them,” he continued.

The haring ibon

A stuffed Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) looks as if it just landed at the museum. Enclosed in a glass case, one could see its feathers, talons, and beak from every angle. But stare it eye-to-eye and it will definitely strike you.

Many observations like this can be made in its natural history collection, the oldest zoological collection in the Philippines. It also has an impressive number of diversified specimens of flora and fauna from around the world.

It was, in fact, this collection that launched the UST Museum. In his book on the UST’s history, Fr. Fidel Villarroel, O.P. wrote that the University’s Museum of Natural History was established in fulfillment of the new system of secondary education decreed in 1865.

The mandate required first-class colegios to have one as a teaching aid for students. The raison d’être of the museum was thus academic. Professors of the University rummaged through Philippine forests to look for specimens, and some of them were given by the network of Dominican missionaries.

Fr. Casto de Elera, O.P., the museum’s second director whom José Rizal got to know personally during his stay at the University, undertook a lifelong project of classifying the entire fauna collection.

His work eventually culminated into a monumental catalog of all Philippine fauna known up to 1895. It was “the first work of Zoology in the Philippines,” as written in Fr. Villarroel’s book.

Described by Fr. Elera as “richer and more varied than many museums in Europe,” the UST Museum has already been a world-renowned institution. It even clinched awards in international expositions during the 19th century, and the Natural History collection was one of its crowning achievements.

Despite its prestige, the museum continued to be an accessible site of knowledge for Filipino students, in a time when students were bereft of science labs in rural schools.

A work in progress

The tour ends where it opens, and the museum goes forward from where it began. That educational mission continues today—for students, academics, and Filipinos to see.

“That the museum still exists is an indicator that our heritage lasts, is being passed down accordingly, and shown for everyone to enjoy. Because we are still here,” Sayco said.

True enough, the safekeeping efforts of the museum have outlasted the ravages of war, disaster, and now a pandemic, and are still continuing onward with the museum’s conservation efforts.

“To be at the forefront of cultural heritage practice […] will remain our mission and vision, so I think we have to uphold it and be true to our word to protect all of this.”

The museum has also been exploring new ways of presenting its collections to the public, as museums worldwide adapt to new definitions of the “museum” which sprung after the pandemic.

The recent Namjooning-themed exhibit is one example. “It’s about keeping up with the times,” Sayco said.

However, the 153-year-old museum is still a work in progress—an honest trait that owes to its values.

“In the University, you are being taught when you’re wrong and when you’re right. So why not emulate that academic trait into practice? Actually, it’s for the better,” Sayco said. F – Eugene Paul M. Lorenzo

The University of Santo Tomas Museum of Arts and Sciences, UST Main Building, Manila is open on Mondays 10:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m., and Tuesdays to Fridays 8:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. The admission is only free for Thomasians.

You may also visit their official website through https://ustmuseum.ust.edu.ph/ for more information.