words and photos by CHRISTINE JANINE CORTEZ

IT IS not often that people of today will ever lay eyes, nor will they ever get a chance to witness an amorphous anting-anting; an inevitable reminder and a relic of a religious icon for protection, luck, and healing.

Most might say it is absurd to even speak of it these days. It may be true, but not for the people who continue to believe.

Some people even made an art out of it during a gallery exhibit curated by Norman Crisologo titled, Bulong at Sigaw: Mga Kontemporaryong Kulam, Dasal, Anting-anting, at Ritwal (Whisper and Prayer: Contemporary Witchcraft, Prayer, Anting-anting, and Rituals).

Held at Art Informal on Connecticut St., Greenhills East, Mandaluyong City. Together, the exhibit was made possible by Crisologo and 11 other local artists, namely, Don Dalmacio, Beejay Esber, Rocky Cajigan, Ryan Jara, Bree Jonson, Doktor Karayom, Gene Paul Martin, Tristram Miravalles, Leonardo Onia Jr., Neil Pasilan, and Kaloy Sanchez.

Most of the time, the best sort of healing is found within the depths of familiar eyes with arms as gentle as the blowing wind. The purest embodiment of home and surrender, that person is none other than a mother.

In the artwork titled Ina, Neil Pasilan vividly captured a quintessential moment between a mother and her child in this emotionally figurative approach. The heavily textured piece was the first thing one would notice upon entering the walls of Art Informal.

Ina was also one of those artworks that one would appreciate up close and personal because of its impeccably vigorous style of painting along with the alluring personality of a mother as a subject.

Hung and lit in a stretch of the reddened wall are the art exhibits’ crowning glory, the anting-antings (amulets). The curator himself gave light to these religious relics by featuring a collection of 14 legitimate gold-colored 18th-century amulets that are now just products of the country’s religious and ancient traditions.

In the olden days, it became a symbolic artifact that was recognized as a trophy in times of war or perhaps a battle gear that served as protection. It represented many peoples’ faiths and beliefs. It held certain prayers, orations, and devotions of different kinds, and like any other superstitious elements, it also came with a ton of criticism.

Truly, there is no surprise in that, but to the same extent, it is quite unfortunate to think how much it meant a lot before and seems so insignificant today.

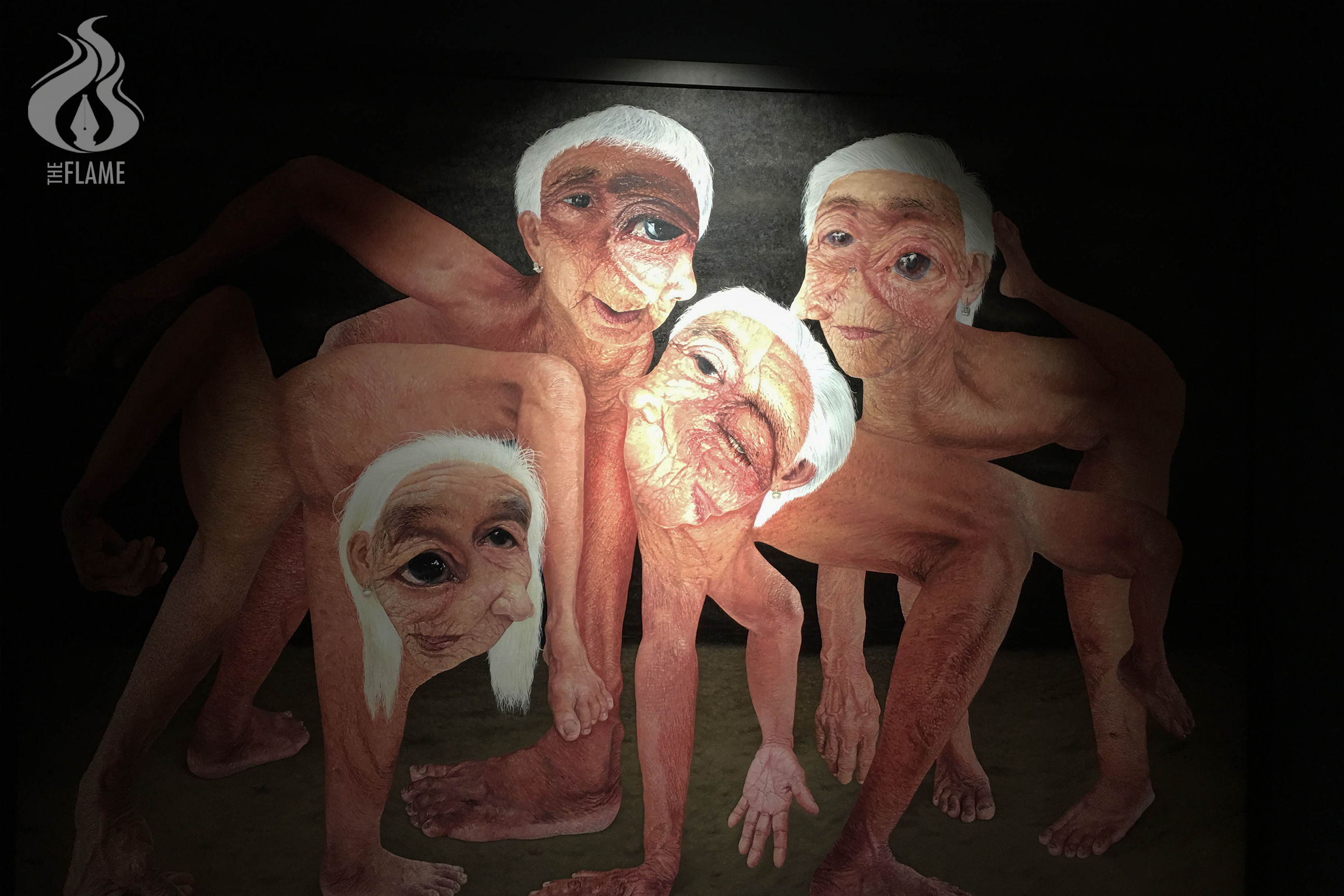

Upon seeing the work of Jara, titled Twisted, a few might note the uncanny way of showing parallelism from the rest of the pieces that appear exactly to their expectations of the event.

From there, it was only logical to mention that whenever people attend exhibits with definite subjects, normally, they come to see something closely related to the title or theme. On the other hand, the surprising factor it generated to the viewers was the quality that makes artworks worthy of another look — perhaps, even more.

For others to see it only as disturbing and unnatural is just the worst impression it deserved. It’s also worth noting that the artist’s choice of subject — the four aged and white-haired faces with intensely rendered skin as textured and visible as the sun — was what made the art piece a surreal sight to behold.

Jonson’s painting, titled in French, Ménchanceté, oligarchie, pléonexie (Are you thinking what I’m thinking?) was the largest piece in terms of size. It showed a hound of dogs that appears to be running or chasing one another in the woods.

Jonson has been known for always using animals, particularly dogs, as lead characters for her art pieces.

Truth be told, not everyone in today’s modern society will stop on their tracks just to pay homage to an artifact imbued with Philippine folklore. It’s controversial and its purpose in society is long served and gone.

From zero to one, almost no one from those who were born in the 21st century will ever remember what it really looked like, nor will they even care what it is all about.

From time to time, people will continue to speak of it, but not everyone will earnestly appreciate its contribution to the life of early generations and the Philippine folklore as a whole.

Although it’s not something that modern people grew up knowing, it’s still a part of history, and it’s only acceptable to maintain its presence in society, at least in thoughts or forms of art. F

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Vol. 55, Issue No. 1 of the Flame. View the entire issue through this link: https://issuu.com/abtheflame/docs/the_flame_vo._55_issue_no._1?fbclid=IwAR2a6lRhIqbWS0O29KnkGuhOGutDrqFfoPGkXUOeyaApRGmi_gFdWj0V4js